She speculated in whiskey and currencies to afford her MBA

The Soviet Union had collapsed, Kazakhstan had become independent, and Dana Minbaeva was 23 years old and in possession of a useless degree in mining engineering. She had to do something drastic. Today, she is a professor and the Vice President of International Affairs at CBS.

“It’s like being at the doctor’s,” says a woman and laughs, as she and another CBS alumni leave Dana Minbaeva’s office on the second floor at The Wedge.

Their meeting had gone over time, and I was waiting for my turn to speak to the Professor of Strategic and Global Human Resource Management and the Vice President for International Affairs at CBS.

I had interviewed Dana Minbaeva and Martin Jes Iversen a month earlier about the work of the new international troika at CBS, and it was during that interview that I realized that I had to do an article about Dana Minbaeva and her educational background.

She mentioned something about learning English at the age of 24, holding a university degree in mining engineering, and coming to CBS at a time when only 15 – 20 of their faculty members were internationals.

I left Dana Minbaeva’s office ninety minutes later, flabbergasted by the story she had just told me.

Survival of the fittest

Kazakhstan 1993: Dana Minbaeva is 23 years old and has just graduated from Karaganda Polytechnic Institute with a degree in mining engineering. After six years of physics, mechanics, mathematics and chemistry at the university, she knows everything there is to know about how to build a coalmine and select the right machinery for mining and production. There’s just one catch.

The coal mining industry is on its knees in 1993.

The Soviet Union collapsed two years earlier and Kazakhstan was made independent. And on top of that, easily accessible oil reserves have been found in the newly established Republic of Kazakhstan, which means that all investments and resources are put into oil drilling – not coal mining.

“I remember the day Kazakhstan announced its independence – December 16, 1991. It was a cold and gray day. The streets were unusually quiet and there was an empty feeling of no past and no future. But there was a present and there was hope,” says Dana Minbaeva and continues:

“Those days were all about active survival. Nowadays we call it ‘entrepreneurship’. Lots of start-ups and entrepreneurs were grasping at every niche left by insufficient governance and/or an unstable market.”

No one grows by holding on to the same leadership position over a long period of time

Dana Minbaeva

During the time of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan – like the other 15 Soviet republics – was highly dependent on materials and goods produced in other regions of the Soviet Union. The government intentionally wanted to create interdependence between republics to secure the union.

After the collapse, this ‘interdependence’ resulted in strange and inexplicable shortages. For example, the city where Dana Minbaeva lived suddenly ran out of matches. The factories producing those in the southern region of Russia didn’t experience any demand (due to the canceled contracts) and stopped production. As a result, the whole northern region of Kazakhstan, where Dana Minbaeva lived at that time, was out of matches for two months.

“During those months, matches became the most sought-after product. We would exchange matches for other products in high demand, like sugar,” says Dana Minbaeva.

Like many other Kazahks, Dana Minbaeva started her own business with a friend, as her university diploma was pretty much useless in Kazakhstan. They bought and sold various products, and at the same time, Dana Minbaeva started taking accounting classes to get a better insight into how to run a business, as it was a constant struggle just to survive.

Master of speculations

1993 became 1994, and Dana Minbaeva was not so sure about her future.

“I stopped what I was doing and thought to myself: Do I want to continue ‘just surviving’ or do I want to do something different?” she remembers asking herself.

She decided on the latter as she had come across an interesting MBA taught by foreign professors at KIMEP University in Almaty, Kazakhstan. KIMEP was supported by the EU’s TACIS (Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Independent States) and USAID (United States Agency for International Development) programs, so everything was taught in English.

I couldn’t pronounce ‘rød grød med fløde’, but after some time and significant effort, I was able to follow a conversation

Dana Minbaeva

The first year cost $300, and to get in you needed to pass two tests, English and math at university level. Dana Minbaeva could not speak English as she had only had it for one year in school, and $300 was a lot of money back then. But that did not stop her.

Dana Minbaeva got herself an English textbook and cassette tapes of English lessons for her Walkman (a portable audio cassette player – Ed.). And to get the $300, she started speculating on the currency exchange market.

“At that time, the infrastructure of the financial market in Kazakhstan was very slow and inefficient. This meant that I could buy currencies (US dollars) in one city, travel to another city overnight, and sell them at a higher price in the morning. By doing that, we could precede the market for about 24 hours. However, sometimes we were unlucky or too slow, and the net income was only $5 per trip. I spent so much time travelling by train, but then I had the time to study English,” says Dana Minbaeva and explains that she studied English extensively for six months, before doing the test.

“To me, it wasn’t a question of whether or not to learn English. It was a matter of doing things differently,” she says.

Besides speculating on currency exchange markets, Dana Minbaeva worked two night shifts a week at a counterpart to Falck from 5pm to 9am.

In February 1994, she had got the money to finance the first year of the MBA, and was ready to do the entry exam. She got in at the beginning of March.

“I’m still ashamed about making money on spirits and tobacco”

Dana Minbaeva had gotten into the university of her dreams, KIMEP University in Kazakhstan, but it was not exactly the easiest of dreams. In fact, it was ‘another kind of survival’, as Dana Minbaeva explains.

“Everything was new. We had to study things like microeconomics and macroeconomics in a completely new way, and everything was in English. But we had to perform, as we were part of the elite, and you could really feel the pressure from all directions,” she says.

And not only did she have to study hard for the MBA, she also had to figure out how to save up another $300 for the second year of tuition.

“Paying for the second year was a little easier, as I speculated in markets instead of currencies. The demand for sugary drinks, spirits and tobacco was huge. The retail market was offering good margins, and none of the large trading houses had their own distributors or retailers. So, it was an easy market to earn money on,” says Dana Minbaeva and adds that she still feels ashamed about making money on spirits and tobacco.

“I stopped my ‘entrepreneurship’ the day I paid for my second year at KIMEP, but I had to continue working,” she says.

A fateful meeting

During the second year of her studies, Dana Minbaeva started working as a research assistant for a professor at the university. One day, not long to go until her graduation, the Danish firm, Rambøll, came to the university to host a meeting, as they were trying to recruit local faculty members for an EU project. Dana Minbeava was passing by the open door to the auditorium and a female voice speaking in a Danish accent caught her attention.

She walked into that meeting, and one week later she had signed a contract. Ten days after her graduation on June 1, 1996, she would be off to Denmark to visit CBS and learn about Danish society.

Dana Minbaeva remembers that at the time of her visit in 1996, only three of the faculty members were foreigners. Four years later, after having lived out of her suitcase as she traveled between Europe and Kazakhstan, Dana Minbaeva came back to CBS to do her PhD in September 2000. The number of foreign faculty members had gone up to about 20.

“We all knew each other, and it was easy to host dinners at home,” she recalls.

Today, 48 percent of the faculty members are internationals.

“I cannot pronounce rød grød med fløde”

When Dana Minbaeva arrived at CBS to do her PhD, she was a native speaker of Kazakh and fluent in Russian and English. But it wasn’t enough.

As she was one of the few foreigners, not all meetings were held in English, and Dana Minbaeva did not want to insist on them being English.

“Sitting through a meeting or a gala dinner, and not being able to follow a conversation, gave me a bitter feeling. So, I said to myself: you don’t want to feel like this, learn Danish. And it helped. I couldn’t pronounce ‘rød grød med fløde’, but after some time and significant effort, I was able to follow a conversation. You cannot believe what a difference it makes to be able to understand people around you at the bus stop or in the shops. It’s as if you can ‘hear’ again,” she says and adds:

“Today CBS does a lot in terms of supporting the international faculty members through language training, and we have had a very well-thought-out language awareness campaign. But I also think the international faculty needs to take responsibility and ‘lean in’ for instance, by learning basic Danish. At least to a level where they can follow a conversation at a bus stop.”

What will people say at your farewell reception?

Four years passed, and Dana Minbaeva defended her PhD in Economics and Business Administration in 2004, but she could not continue working at CBS, as there was a hiring freeze. Instead, she spent a year of doing ‘academic entrepreneurship’ – combining teaching at the University of Copenhagen, Roskilde University and CBS, which gave her flashbacks to the time after her graduation from the Karaganda Polytechnic Institute.

That was right up until she applied for a position as Assistant Professor at the Department of Intercultural Communication and Management at CBS in 2006. And she got it.

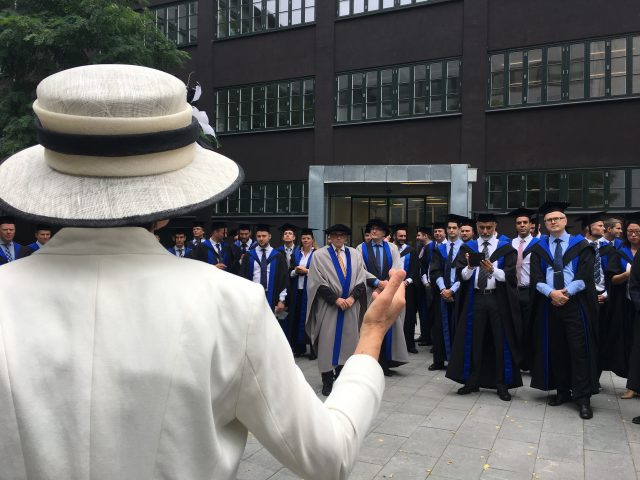

Dana Minbaeva has had her office at almost every CBS building. Right now, it is on the second floor of the Wedge. (Photo: Anne M. Lykkegaard)

Since then, Dana Minbaeva has climbed the academic ranks, received numerous national and international awards for her research and teaching, and gained administrative experience in leadership positions. All this has given her new opportunities, but it takes up a fair amount of time.

“Right now, my biggest problem is time. The job as Vice President of International Affairs is so cool. I could drop everything just to do this because it’s so exciting with so many opportunities and it’s very entrepreneurial. But if I drop what I do as a researcher and professor, I would be on ground zero like this,” she says, snapping her fingers.

Her MBA diploma from 1996 hangs on the wall behind her. It was handed over and signed by the President of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev.

Dana Minbaeva pauses and recalls the words of a dear friend.

“He said to me: ‘Dana, whatever job you take, give yourself time and decide how long you’re doing it for, and think about three things that people will talk about at your farewell reception.’”

“So, I have given myself time. It’s going to be four years, maximum eight. No one grows by holding on to the same leadership position over a long period of time. And I have identified three things that I want to achieve, but I’m not going to tell you what they are,” she says and laughs.

“Because otherwise in three – four years, I’ll come knocking on your door and say, so Dana, how did it go?” I reply, while Dana Minbaeva nods and keeps laughing.

Comments