The power of the wallet: We vote with our money

(Photo: Shutterstock)

As consumers, do we have the power to force businesses to change their behavior, improve working conditions, and become sustainable? Yes, claim two CBS researchers, who share their views on the matter in the wake of the Nemlig.com case and give three pieces of advice.

Customers ordering groceries through the delivery service Nemlig.com were probably left gawking when anonymous chauffeurs and warehouse workers shared testimonies about their working conditions at the online supermarket.

Extreme time pressure, up to 15-hour working days, a fining system for not living up to the company’s delivery standards, and dangerous working conditions, just to mention a few of the accusations. And the working conditions have now been criticized by the Danish Working Environment Authority.

So what now? The stories in the media, the comments from ministers, and latest, the critique from the Danish Working Environment Authority, are likely to lead to some kind of change, but what about the customers and consumers? Do we have the power to make Nemlig.com and other businesses act differently and take another direction if we demand it?

The short answer is: yes, we do. But as with many other aspects of life these days, the answer is multifaceted.

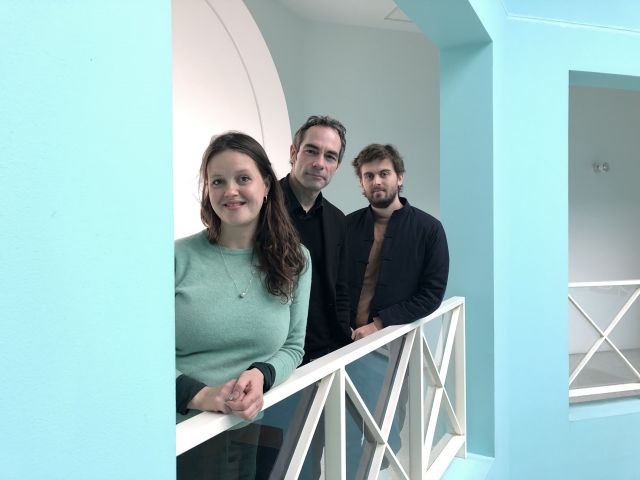

I have reached out to Andreas Rasche, Professor of Business in Society at the CBS Centre for Sustainability and Meike Janssen, an Associate Professor with expertise in consumer behavior at the Centre for Sustainability, to get their views on the matter, but also to discuss whether we, as consumers, can be nudged to change our behavior.

“Individual consumers have very little chance of checking the production conditions of the products and services they consume. We as consumers only see the final product at the point of purchase,” says Meike Janssen to kick off our discussion.

“But it is important to remember that we vote with our money, so, in that sense, we have huge power over what companies should and should not do,” she continues.

Practice what you preach

According to both Andreas Rasche and Meike Janssen, the segment of sustainably minded consumers is on the rise. We want to know whether the cacao beans in our chocolate are from Fairtrade, whether a product contains palm oil, and by knowing where a product has been produced, we can make up our minds whether to buy avocados from Spain or Peru.

This is also known as “consumer sovereignty”, explains Andreas Rasche, and covers the possibility of deciding for ourselves what we buy and what businesses we support.

Taken to the extreme, this can result in consumer activism where businesses have given in to protests from customers and organizations.

Meike Janssen explains that, for example, Shell UK had to abandon its plans on disposing the North Sea oil storage and tanker loading buoy, Brent Spar, in deep Atlantic waters about 250 kilometers from the west coast of Scotland, after Greenpeace organized a worldwide, high-profile media campaign against this plan in 1995.

The campaign led to public and political opposition, including a widespread boycott of Shell service stations.

But these types of cases are rare and are not initiated by mainstream customers.

“We need someone to put terrible working conditions or unsustainable practices on the agenda. Because then we will see movement among consumers, but it depends on a group of very interested and well-informed people, often journalists, who get the ball rolling,” she says.

Andreas Rasche explains that, in general, how we consume does matter, as it sends a signal to companies that we take their behavior seriously. But when looking around, Shell still has service stations around the globe.

“Well, history tells us that consumer behavior is hard to change. We have seen boycotts of Amazon and consumers staying away, but the majority are pushed back into their arms. I wouldn’t say that consumers don’t care, but they find it too inconvenient to go elsewhere. Which is why we need these debates. We need to continuously discuss what we want to accept,” says Andreas Rasche.

He explains that most of us are convenience shoppers. And in a hectic daily life, convenience wins.

“Maybe switching from Nemlig.com to Coop or Føtex seems easy, but the switching costs are higher than we think. If you look at gasoline, you can get it from Circle K or Shell. That doesn’t matter. The switching costs are low. But with online supermarkets, you have to create a new account, make a list of favorite items and get used to the setup, so switching online supermarkets is not so convenient. Theoretically speaking, therefore, we have a lot of power, but in practice we don’t always use it.”

He explains that when popular media run statistics and surveys claiming that 70% of their customers want to shop differently and more sustainably, that does not correspond with reality.

“There is an increased willingness to do what is right and shop sustainably and ethically. But when you look at how people actually behave, there’s a big gap. And that has a lot to do with what researchers have called ‘social desireability bias. There is a difference between what we say we do as consumers and our actual shopping behavior. Many consumers say they intend to buy Fairtrade coffee because it is the socially accepted answer. However, only few of is actually do it, because we usually have to pay a price premium,” he says.

Power to the people

Meike Janssen acknowledges that being a sustainable consumer is hard work, and she does not believe that consumers should bear sole responsibility for rectifying poor working conditions or holding businesses accountable for their stated sustainability.

“What kind of market is it where consumers need to be hypercritical of everything they buy all the time? Then something is fundamentally wrong, and we need stronger regulations and politicians stepping in. There is no way that we can always check up on everything, and we have the right to assume that we can trust the products being offered, and trust that products labelled as ‘sustainable’ are truly sustainable,” she says.

For example, the Danish, certified label for organic produce – Ø-label – is a way to assure consumers that the product is organic. The label was introduced 31 years ago, and both Meike Janssen and Andreas Rasche claim that more labels like that would create more transparency on how products have been produced.

“Politicians have the power to create more transparency. Right now, we get confused by the sheer number of different labels, many of which only offer limited transparency. Who can tell the difference between the Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade labels? Only highly-trained experts. I can’t tell the exact difference, so we cannot expect that from consumers,” he says.

Meike Janssen emphasizes that the labels with the strictest standards are currently those based on government standards or NGO standards, and those are also the ones perceived as trustworthy by consumers

“Labels issued by industry-driven initiatives are often at the borderline to green-washing because the underlying production standards are not truly sustainable,” she says.

But what would it take to introduce labels with stricter sustainability standards? And will we get there?

“National governments and the EU have a responsibility to enable consumers a so-called informed choice. But it remains to be seen whether EU-labels with stricter standards will be introduced in the near future, for instance in the fashion market or the fishing industry. There’s a lot of industry lobbying going on, so in the end, it’s probably a compromise at the expense of sustainability,” she says.

It always comes back to the monetary dimension

Andreas Rasche

Investors are another group with a lot of power to change how businesses produce and operate, according to Andreas Rasche.

“Investors can also put pressure on businesses. They can move their money. And they can choose only to invest in businesses where the risk of a consumer boycott is low,” he says and adds:

“It always comes back to the monetary dimension.”

Better consumer behavior

When we go grocery shopping, we often have plenty of options about whether to buy carrots, jam, sliced meat or dishwasher detergent. And when choosing a product, we can have different criteria in mind. Maybe price is the most important criteria, maybe the Ø-label is, or that the product is locally produced or does not contain perfume and allergens.

And although we can choose for ourselves what we want, we can also be nudged to make better choices.

Meike Janssen explains that product labelling, and especially mandatory labelling “are extremely powerful”, meaning that labels should be on every product, not just sustainable products, to disclose information on production processes etc. She gives an example:

“The mandatory labelling of eggs with the production system made a major change in consumer demand, and in response, also on the production side. It came into force across the EU in 2004, and since then, eggs have to be labelled as either from ‘cage systems’, ‘barn’, ‘free range’ or ‘organic’. Once this system was put in place, consumers shunned cage eggs,” she says.

In Germany, the share of eggs produced in cage systems fell dramatically after the introduction of the mandatory labelling of eggs.

In 2002, more than 80 % of the German eggs came from cage system. The figure had gone down to just under 40 % by 2009 and 10 % in 2014, according to statistics from Meike Janssen.

Meike Janssen believes that similar labelling schemes are possible for all sorts of production-related criteria, as long as label overload is avoided.

“More mandatory labels for key criteria, such as the use of synthesized chemical pesticides or fertilizers, would be a promising tool for empowering consumers,” she says.

Right now, Meike Janssen and her colleagues from the Consumer and Behavioral Insights Group at CBS are working on research projects where they are exploring the possibilities of nudging consumers towards behaving more sustainably.

The students I teach don’t question whether we need sustainability in a business strategy, and that makes me hopeful

Meike Janssen

“We are developing and testing ways to nudge people into consuming more sustainably, for instance eat less meat and more plant-based food. We are also working on tools that facilitate choosing the more sustainable version of a product,” she says.

Hope in the younger generations

So just to sum up. Do we have any power over business practices? Does it matter if we question their stated level of sustainability and demand better working conditions for their employees?

“Yes, we have the power because we are many, we are well-connected and because companies and corporations are recognizing that they are on the radar and cannot hide everything behind closed doors. And we have good, investigative journalist. In countries like Denmark, we can also afford sustainable consumption. We can afford to pay more for alternatives if they are more sustainable. So we have the prerequisites within reach,” says Meike Janssen.

Especially the well-connectedness, combined with the option of looking up different kinds of information, makes it easier for consumers to make decisions.

“Again, the number of consumers who are actually doing something is rising. It’s easier to make people aware of what is happening. And although it can be hard to win their attention, due to information overload, it’s definitely easier to share information, and arrange boycotts and demonstrations. And that makes a difference,” says Andreas Rasche.

And finally, Meike Janssen cherishes special hope in a certain group of people.

“I have hope in the younger generations. We are a business school, but the students I teach have sustainability high up on their agenda, and they take it as a given that businesses should act responsibly. They don’t question whether we need sustainability in a business strategy, and that makes me hopeful,” she says.

Comments