Partnership with war-torn university grows – 25 Ukrainian students to attend summer school at CBS

Illlustration of Karazin University. The university is one of many Ukrainian educational institutions that has been damaged in the war. Photo: Shutterstock/Ganna Sereda.

Twenty-five Ukrainian students will have the chance to attend courses at CBS for free this summer. The initiative is the result of a partnership between CBS and Karazin University in Kharkiv. “We can do our share as an academic institution to strengthen Ukrainian universities,” says Martin Jes Iversen, Vice Dean of International Education.

V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, often known as just Kharkiv University or Karazin University, is not a highly ranked school and not one that CBS would normally have a partnership with.

“Keep in mind, we are very selective with partners – we did not have any partners in Ukraine before the war. But this is not something we do because we are identifying a highly ranked university. It is something we are doing because it’s important to support,” says Martin Jes Iversen.

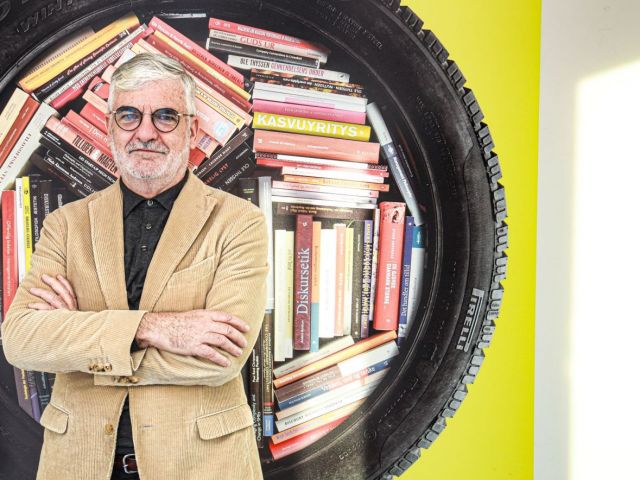

“In this situation it’s a one-way exchange. Obviously, we cannot send CBS students there,” Martin Jes Iversen, Vice Dean of International Education says of the partnership with Karazin University in Eastern Ukraine. He hopes that the collaboration, which has come about as a result of the war, will continue into peacetime. Photo: Caroline Hammargren

The collaboration started after he met a representative from Karazin University last spring at a conference for members of Aurora, an alliance of European universities.

Beyond the connection through Aurora, Martin Jes Iversen says there are two reasons for CBS work with Karazin:

“One is that it’s a university in need – they are so close to the war and affected by it. The other reason is that it is a large university with a business school where we can make a difference for a lot of people.”

We know, of course, it’s a very small group, but it’s not trivial.

Martin Jes Iversen, Vice Dean of International Education, CBS

Although the partnership is with Karazin University, CBS aims to collaborate mainly with Karazin Business School – part of the university, which itself dates back to 1804.

“It’s existed for many years and it’s part of really strong academic traditions, maybe even stronger than CBS, at least much older – and, we don’t have any Nobel Prize,” Martin Jes Iversen says.

Karazin University can boast three Nobel laureates.

The university is located in Ukraine’s second largest city Kharkiv in Eastern Ukraine, only 40 kilometres from the Russian border. It is an area that has been heavily bombarded during the war and still is. Many of Karazin University’s historical buildings have been destroyed or heavily damaged – a video from the university shows blown out windows and hallways full of rubble.

According to the science journal Nature, one out of four (27%) Ukrainian research and higher education institutes have suffered war damage.

Despite that, teaching has continued online.

When Martin Jes Iversen met professor and lawyer Tetyana Kaganovska from Karazin University at the conference last April, shortly after Russia’s invasion, she told him: “We continued through the First World War, we continued through the Second World War, and we will also continue through this.”

Summer university for Ukrainian students

After that, the first steps towards a collaboration were initiated and last summer two students joined the CBS International Summer University Programme. This year, the plan is to scale up to 25 students from Karazin University.

“We know, of course, it’s a very small group, but it’s not trivial,” says Martin Jes Iversen.

The slots have been allocated for students from Karazin, but they will still have to meet entry requirements and apply. The students have the chance to stay six weeks for two summer courses. CBS is applying for funds to cover their housing and transport costs.

The education system here is different from Ukraine. If you have not read anything for a class, you will not understand anything, so you have to prepare all the time. In Ukraine, you just attend classes and it’s not that important to do schoolwork out of university.

Vladyslava Boiarska, exchange student from Karazin University

Vladyslava Boiarska, a psychology and sociology student at Karazin University, is one of the students who attended last summer.

She had planned to just stay for the summer course, but her professor, Kai Hockerts, suggested the possibility of applying for an exchange semester at CBS.

“Thanks to him, I’m here,” she says, smiling as she glances down on the open hall of Solbjerg Plads.

“I like the buildings at CBS. In Ukraine, the campus is so old compared to this. I feel I’m more productive and motivated to study when everything is so beautiful.”

Vladyslava Boiarska likes the social events at CBS. She was really happy with the crash course for exchange students during introduction week. This semester, she applied to be a crew member herself and helped organise events for the new exchange students arriving. Photo: Caroline Hammargren

She left her hometown Kharkiv on the day the war broke out.

“On the morning when the war started, we packed our stuff and moved to Poltava, where my relatives live, because it was safer. At first, everyone thought it would end in three days or a week. No one thought that it would be a year or more. We just took two T-shirts and a sweater, documents and money,” she says.

After a month in Poltava, she secured an opportunity to go on exchange in Poland in the spring.

“I didn’t want to go as a refugee. I applied to go as a student to have more opportunities,” she says.

From there, she eventually came to Denmark to study social entrepreneurship in the summer.

“It was so cool because the education system here is different from Ukraine. Here you take responsibility for your studies. If you have not read anything for a class, you will not understand anything, so you have to prepare all the time. In Ukraine, you just attend classes and it’s not that important to do schoolwork out of university.”

Ukraine fears brain drain

Now Vladyslava Boiarska is studying at CBS, while in the evenings she keeps up with her online classes in Ukraine, which are recorded. The plan is to finish her degree in Ukraine and then apply to at CBS.

“I want to stay and finish my studies here, but I want to go back to Ukraine after the war ends. I want to help to rebuild the country and I think I can do it because of the knowledge I have gained here. I want to go back because it is my home country and I miss it a lot.”

Martin Jes Iversen says that CBS has received signals from Ukrainian representatives that they want to avoid a brain drain.

“We have to be cautious to find that delicate balance, providing opportunities to students in a difficult circumstance, but at the same time supporting them to still have a foothold at home in Ukraine. A nice way to do that is the summer university.”

CBS is also exploring other ways to offer academic support. The idea is for faculty at Karazin Business School to identify CBS courses that are relevant to theirs.

“We will see if we can build a bridge between professors at the two institutions. Our professors could provide guest lectures, various types of support, or it could involve group work between students.

“I think one of the most beautiful ways that CBS can help is through intellectual support. CBS can contribute to the continuation but also development of such an old university. We can do more in that respect than through financial support. Maybe we can help to redefine what kind of business school will come out of this terrible situation.”

New ways of partnering

Ultimately, it will be up to the professors to find a good fit – and the time – to collaborate.

So far, Karazin Business School has expressed interest in the International Business programme and initiated talks with programme director Bersant Hobdari to chisel out a collaboration.

“At faculty level, we’re thinking of introducing course coordinators and teachers on both sides and have them develop common teaching materials or guest lectures, or anything that is feasible under the circumstances,” he says.

That is not how CBS normally works with partner universities, but unusual times call for unusual measures.

It will definitely provide a network in an area of the world where little interaction has existed so far. And faculty and students will get to learn a lot about carrying out business in highly unstable and conflict situations.

Bersant Hobdari, Programme Director, BSc in International Business

Beyond supporting Karazin, Bersant Hobdari thinks the collaboration could provide CBS with a different perspective of international business.

“It will definitely provide a network in an area of the world where little interaction has existed so far. And faculty and students will get to learn a lot about carrying out business in highly unstable and conflict situations,” he says.

The initiative is still at its early stages. Discussions are ongoing over email with faculty in Ukraine where internet connectivity and electricity are unstable.

“Given the circumstances, it’s not super quick. It will take some time. At best, we’re looking at the next academic year,” he says.

Down the line, Martin Jes Iversen hopes the collaboration will continue into peacetime.

“I see CBS playing a role, also in the medium to long term. What kind of university will constitute itself after the war? The approach of focusing on a specific business school has something to it. We hope in the future that we can develop the collaboration and discuss what is needed when we come to the rebuilding. Hopefully, soon, there is a more peaceful situation.”

Comments