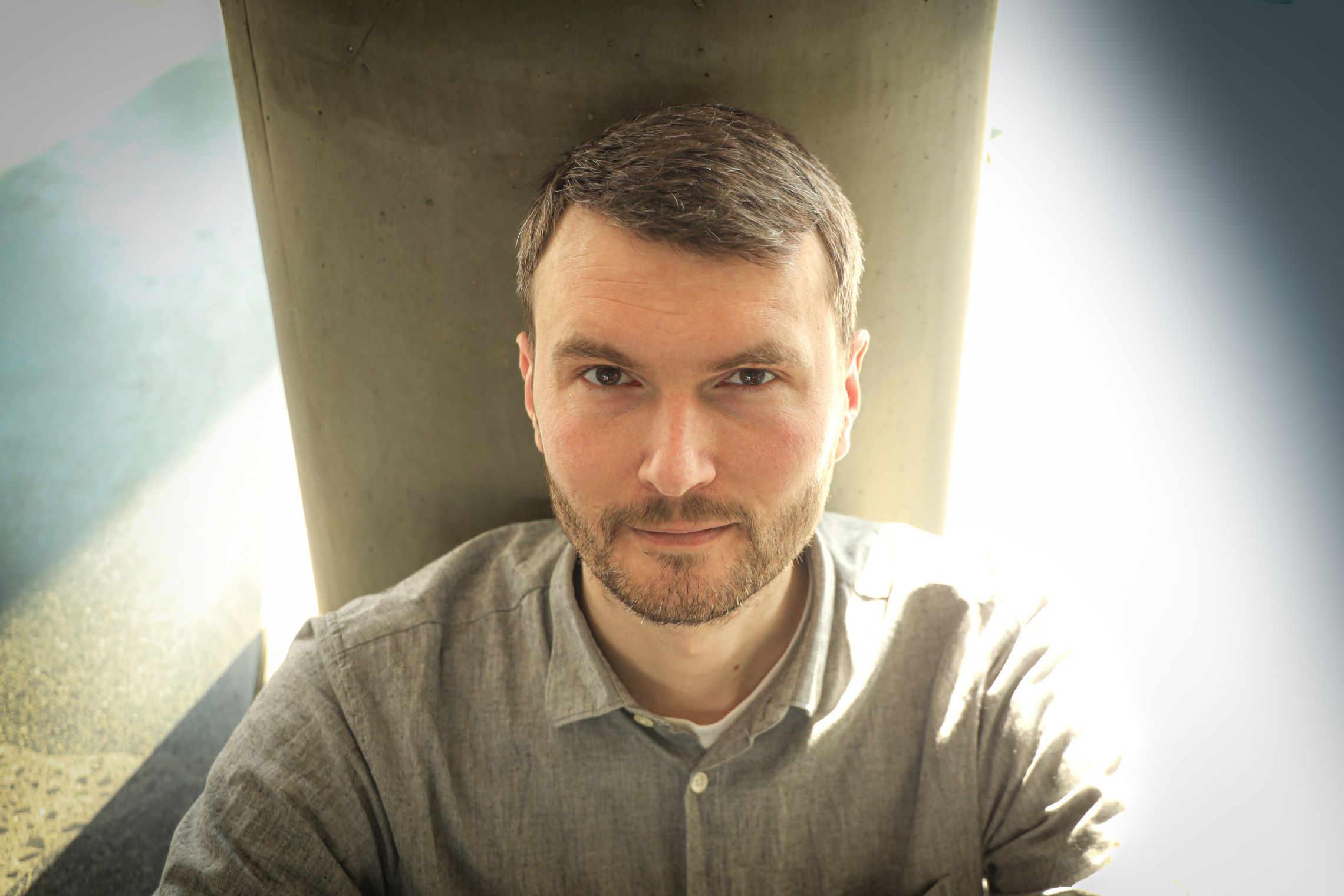

“I’m not changing my research”

Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard, CBS Professor with expertise in Chinese politics, describes what is happening in Hong Kong with the instatement of the National Security Law as “unfortunate, worrisome and sad”. But he is not worried about his or other researchers’ academic freedom. At least not yet.

China’s government has bared its teeth at Hong Kong with the instatement of the new National Security Law this summer.

In short, the law criminalizes acts of subversion, secession, terrorism and foreign collusion, but it does not apply exclusively to Hong Kong residents. The legislation also covers offences committed against Hong Kong and the Communist Party of China from outside the Region by individuals who are not permanent residents, as described in Article 38.

The new law has not only caused riots in the streets of Hong Kong, however, as several hundred international researchers have also stepped in to aid their community.

In a statement and petition issued by the British Association for Chinese Studies (BACS), the association writes that the new security law is an assault on academic freedom.

Especially Article 38 of the law will “compromise freedom of speech and academic autonomy, creating a chilling effect and encouraging critics of the Chinese Party-state to self-censor,” they write in the statement, which has been signed by several hundred researchers from across the globe – including Danish postdoc Line Marie Thorsen from Aarhus University, and they continue:

“The National Security Law makes it an offence – punishable by a lengthy prison sentence – to criticize the rule of the Chinese Communist Party or to make subversive statements about the Party and its rule, regardless of where in the world an individual is based and regardless of their citizenship.”

But what does the law and the situation in Hong Kong reflect? To answer that question and outline the situation in Hong Kong, CBS WIRE has reached out to Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard, Professor at the Department of International Economics, Government and Business at CBS.

The professor has been following and studying China since the late 70s and has expertise in China’s political economy, including state-Party business relations and the role of the Communist Party of China in the current modernization process.

And he is not surprised by how things have panned out politically in Hong Kong – although the tightening of regulations is coming earlier than expected.

“What has happened in Hong Kong is unfortunate, worrisome and sad. I have been following the situation, but it does not surprise me that it has come to this. Hong Kong returned to China in 1997, and China will not let it go,” he says.

I have never felt subject to censorship. I have always pursued the topics I believed were important and interesting

Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard

Moreover, the Hong Kong government has mishandled the situation, which has made things even worse, he argues.

“Already in 2003, Hong Kong was asked to instate a similar law, but the government of Hong Kong held off because of protests. Now, the law has been forced on them from outside. If the Hong Kong government had succeeded in introducing the law themselves, it would have been a different situation,” says Kjeld Erik Brødgaard and adds:

“Now there are no optional ways out for either side. This has resulted in a bad situation for especially the youth, who had dreams of a different society. Also, this tightening should not have arrived yet. Hong Kong is supposed to function as an entity in its own right until 2047.”

No cases – yet

Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard is, like the British Association for Chinese Studies, against the law. He also sees how the law could constitute a potential assault on academic freedom and freedom of speech. But so far, he has yet to see any examples of cases that worry him.

“I have good and recognized colleagues in Hong Kong who I know express themselves critically about China, but they are still in their positions. And I haven’t heard about researchers from universities outside of China that have got in a pickle for criticizing China in this respect. But it can potentially happen,” he says and adds:

“In a way, I think we are overdramatizing a little. It’s not that all the critical voices have been silenced. Of course, that’s easy to say when you don’t live in Hong Kong, and especially the youth have suffered a defeat, which is sad. But for those of us who work with China, I can’t see how this law will affect us. At least, I don’t have the intention of changing my research, and I don’t think others should.”

Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard reminds us that Hong Kong has been part of China since 1997, and therefore it is hard for Western governments to change what is happening.

“You can express your regret and criticize the law, and you can be sad that things have come this far and that they have been unable to negotiate. But we cannot deny that Hong Kong is a part of China,” he says.

Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard also teaches at the Sino Danish Research center north of Beijing, and he has never personally experienced having to self-censor or choose carefully what content to use.

“I have never felt subject to censorship. I have always pursued the topics I believed were important and interesting, and the Chinese students have read the same as the Danish students. I don’t understand why researchers would feel like they had to self-censor. They have to be honest about their interests and not think about censorship,” he says.

“I would be worried if”

The new law is only a few months old, but what kind of developments would cause Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard to worry?

“The moment good and recognized colleagues in Hong Kong are being fired or in any way having their freedom of speech compromised, I would be worried. I definitely would. I believe in the freedom of research, so if that happens, we must sound the alarm,” he says and adds:

“I would also be worried if the Chinese embassy sought me out and had noticed something about my work, or if I had a visa to China denied because of something I had written. Then I would be worried. But that’s not happening.”

For some, the current situation in Hong Kong could result in less collaboration, but Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard believes CBS and Denmark should take a stand and make sure to remain involved in China.

“We cannot close our eyes to China. It’s a superpower in line with the U.S. We cannot say that we no longer wish to deal with China, since as a collaborator it’s too important for Danish businesses and also if we want to succeed with the green transition. We can’t take climate action without China,” he says and continues:

“Therefore, we need an ongoing dialogue with China in which we can also tell the Chinese authorities when we do not agree with them. That’s the way forward. And that’s why we need to study China and understand the political discussions if we want any say in the direction China is taking.”

Comments