Freedom of research at the marketized university?

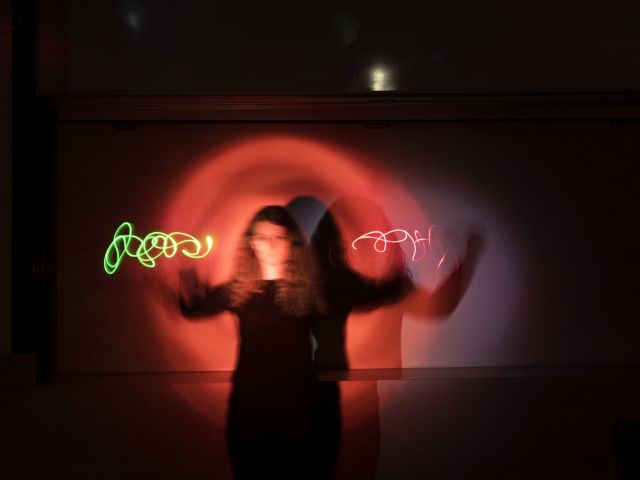

(Illustration by Emil Friis Ernst)

Opinion | 17. Jun 2021

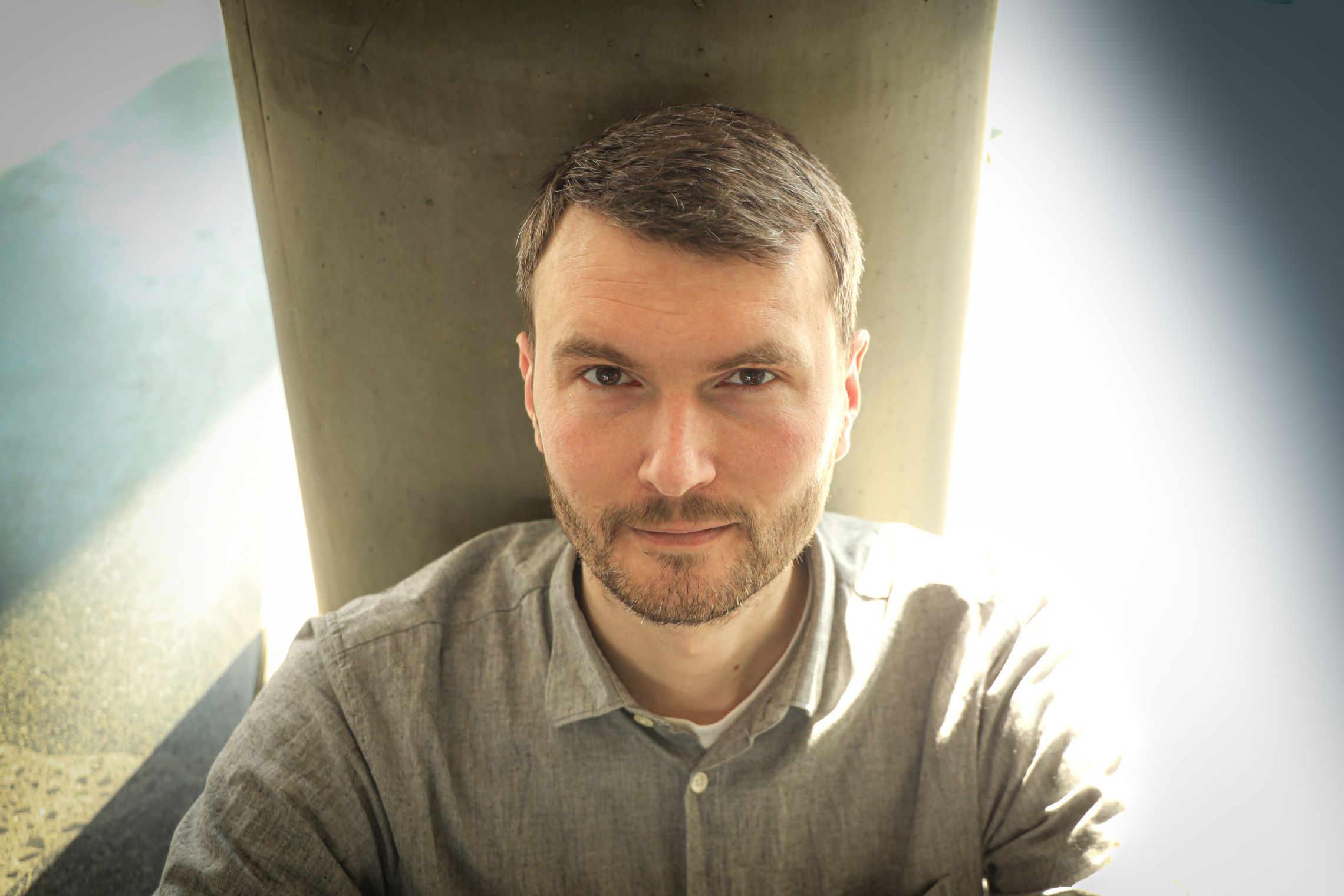

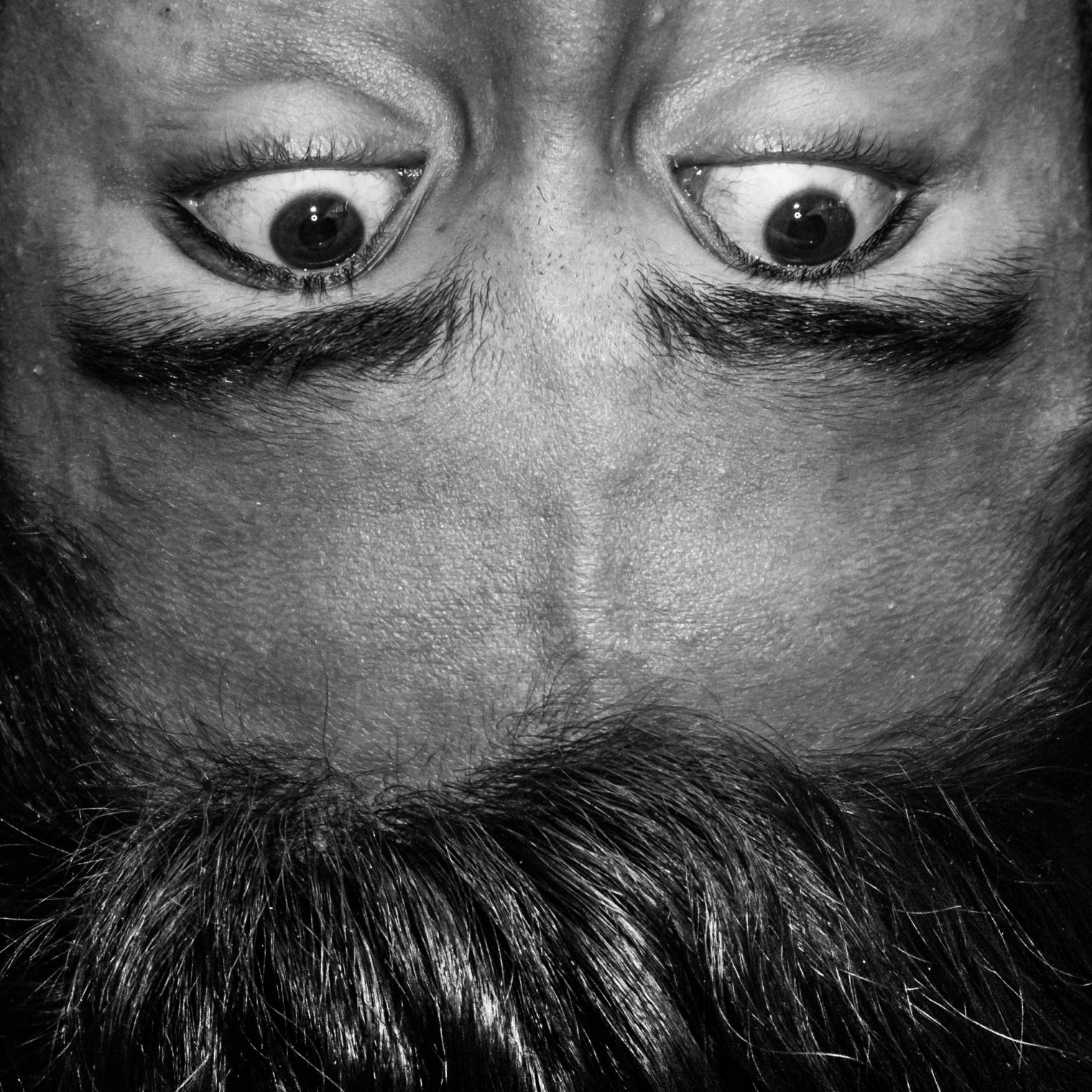

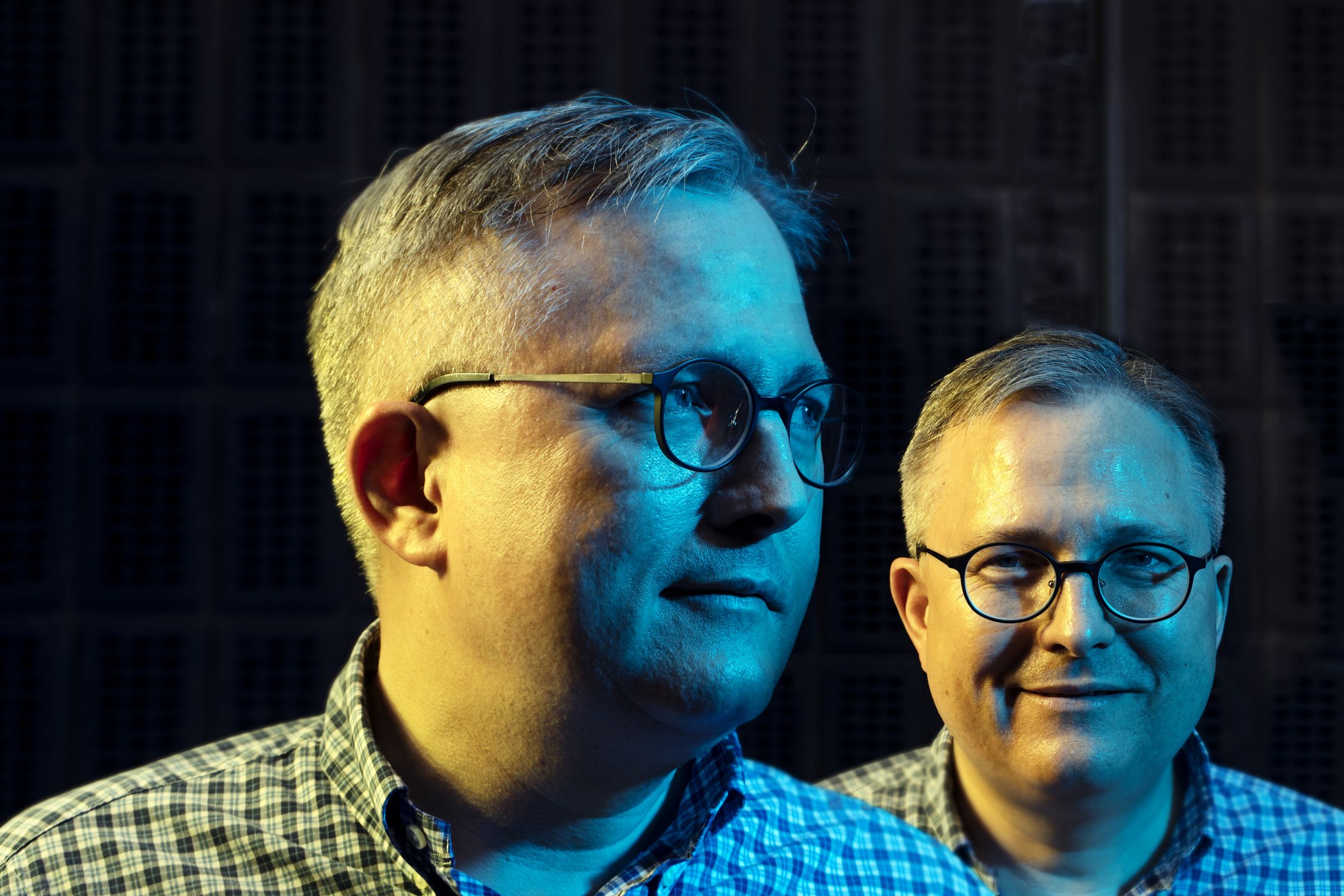

By Mads Peter Karlsen, Assistant Professor, and Kaspar Villadsen, Professor with special responsibilities at the Department of Management, Politics and Philosophy

For some time now, centring on the catchy term ‘identity politics’, a heated debate has been raging about the politicisation of the research that is conducted at our universities. In a nutshell, identity politics is a form of politics, rooted in the religious, ethnic, sexual or other identity of a particular group, that aims to safeguard the interests of that group and ensure that their identity is not violated.

The debate is extremely important, as the theme is crucial for the existence of our universities: it concerns the research freedom of our researchers and universities. However, a serious problem with the debate, already highlighted by a range of commentators,[i] is whether identity politics now takes too much of the spotlight. Not only because no scientific study has yet proven that identity politics is a particularly urgent problem in terms of research freedom, but especially because the question of identity politics diverts focus from the real problem, which is a much more fundamental and structural problem.

For, research freedom in Denmark is currently under pressure. This has been thoroughly documented in e.g. Heine Andersen’s book Forskningsfrihed – Ideal og virkelighed, (Research freedom – Ideal and reality). However, the main source of this pressure is the fundamental and extensive political reforms that have taken place over the past twenty years, resulting in a pervasive ‘marketization’ or ‘corporatisation’ of Danish universities.[ii]

This marketization is reflected in the demand that universities constantly compete on the international market for publications, research funding, scientific labour and students. Today, university researchers have thus become ‘entrepreneurs’ whose most important task is to produce bibliometrically competitive knowledge, generate external funding and offer programmes centred on maximizing candidates ‘employability’. Researchers are increasingly measured and promoted based on their ‘performance’ and ‘innovation’ in these areas rather than their academic skills and knowledge.

At the same time, students today have the doubtful honour of being treated, at the same time, as ‘consumers’, who must be catered for (so that individual teachers, programmes and departments don’t risk bad evaluations or losing their customer base), as well as ‘output’ to be produced as quickly, economically and smoothly as possible, in gigantic auditoriums by the use of innovative digital didactics and group exams. It is indeed telling that educational programmes can now be assessed as to whether they have strong or weak ‘business model’.

The marketization of universities is not only evident in this market focus, but is also linked to an undemocratic, top-down management structure that has been implemented under the ambiguous term ‘Human Resource Management’ and legitimised by prestigious institutions like Harvard Business School and the London School of Economics.

The effect of this transformation of university management, which was fully implemented with the Danish law on universities from 2003, was already visible in a comprehensive questionnaire from 2009 in which 90% of the participating university staff replied that they had no influence on their top managers’ decisions and only half of them felt that they had any influence on their heads of department.[iii] Ironically, in many cases, the remnants of university democracy have been effectively annulled, so that the assignment of programme directors and coordinators no longer happens by election but by management appointment.

Research freedom also includes not being forced to conduct research aimed at specific journals, selected by politicians or the university management

Clearly, the combination of marketization and managerialization, thoroughly documented over the past 15 years, has decisively affected both how the universities organise research, and how the individual researchers carries out their activities, insofar as these twin forces determine the framework that answers the how and what of research.[iv]

As Frederik Stjernfelt noted in a recent commentary to the current debate in Weekendavisen: “Denmark began having problems with research freedom after the law passed in 2003, which introduced employed management at all levels of the universities along with a relatively hollow label of self-governance.”[v]

As Heine Andersen has emphasised, research freedom essentially involves freedom of publication.[vi] However, freedom of publication is not solely a matter of safeguarding researchers against being denied publishing, having publications censored, or being intimidated into self-censorship.

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

Research freedom also includes not being forced to conduct research aimed at specific journals, selected by politicians or the university management based on bibliometric rankings; a selection that is often a far cry from individual researchers’ and research groups’ academic specialist expertise.

Bibliometric indicators and journal rankings are hardly neutral rating instruments that reflect indisputable research quality. They have political and managerial implications that have wide-ranging effects on research practices.[vii]

As David Butz Pedersen, Lasse Johansson and Jonas Grønvad pointed out in 2016: “A number of evaluation researchers find that bibliometry has constitutive or performative impacts, which means that bibliometry does not simply measure research but is an instrument that inevitably influences behaviour in research institutions. The indicators affect how researchers work and who is permitted to conduct research. As shown by Peter Dahler-Larsen, among others, researchers change their behaviour to succeed better in terms of the indicator deployed to measure them.”[viii]

For instance, why publish research on public schooling, the healthcare system, or Danish culture in Danish if one’s career advances far more from publishing on themes in English that fit into international ‘high impact’ journals – and if ones’ leader is uninterested in the former but very concerned about the latter?

Under present conditions, briefly outlined here, university researchers have largely no opportunities for influencing, or even discussing, which bibliometric indicators and ranking lists should be used for evaluating their work. This is highly problematic, considering the extensive discussion, over the past 10 years, in the international research community and in bibliometric research regarding what such ranking lists and bibliometry can and should and be used for, academically and ethically.

These discussions have resulted in the so-called “Leiden Manifesto”, which includes 10 principles for responsible research evaluation supported by the Association of European Research Libraries as well as a long list of researchers in the field of bibliometry.

The spirit of the manifesto can be summarised with a quote from the Danish bibliometry researcher Svend Bruhns: “Journal Impact Factors must be taken very seriously nowadays, because this surrogate indicator is actually used in various places in the world as a direct measure of scientific quality, although everybody can see that a journal’s average impact factor cannot possibly say anything about the quality of individual articles.”[ix]

Bibliometric standards are not only misleading at the individual level. They also have unfortunate, wide-ranging consequences, since they have been a powerful driver for universities to turn their attention towards maximising their international rankings, rather than creating long-term and sustainable research environments.

Another key problem related to using journal impact factors as a neutral and indisputable indicator of quality is that articles can very well be cited for reasons other than their scientific quality. In today’s high-speed media-driven public arena, researchers and journalists sometimes cite articles because they have click-bait titles or represent controversial viewpoints.

This could also prompt a snowball effect whereby an article is cited simply because it has been cited by many other sources. The article then becomes an unavoidable reference that simply must be cited if you wish to publish on a particular subject in a particular type of journal (without that necessarily meaning that the article is of high scientific quality).

Some editors speculate bluntly in actively boosting their journals’ impact factors, for example by publishing about subjects or terms featured high on the Google search engine, or by ensuring that manuscripts contain many references to their own journals. The bibliometric standards also give publishers strong financial incentives to promote certain journals or fields of research.

For example, we experienced that an editor of an international journal demanded that we changed the title of our article to increase its ‘searchability’ or ‘discoverability’. Instead of the title we thought expressed the key points of the article, the editor sent us a list of terms that statistically proved to generate many hits for Google’s search engine. After some discussion back and forth, it became clear that the editor would probably block the article from being published altogether, unless we agreed to use more ‘searchable’ terms in the article’s title.

Consequently, the title of the article was changed from ‘Health Promotion and the Quest for a Well-Balanced Subject’ to a title composed of ‘hot’ search terms: ‘Health Promotion, Governmentality and the Challenges of Theorizing Pleasure and Desire.’

This experience showed us that even a critical sociological journal had embraced the dominant impact and ranking regime to such an extent that the editorial team forced contributors to follow specific strategies for maximizing the journal’s impact.

Despite these critical considerations, which are discussed not only by hippie humanities scholars, but also by hardcore bibliometry researchers, there is still, as David Butz Pedersen, Lasse Johansson and Jonas Grønvad note, “a tendency for bibliometric analyses, once available, to be elevated as the primary source of insight into the progress and quality of research.”[x] This is deeply problematic, since the bibliometric standards then achieve a disproportionate effect on the individual researchers’ opportunities for achieving employment, promotion and research funding.

It is crucial that we give more attention to this deep-seated, uncritical belief in bibliometry, since this quantified measurement of research quality, combined with a self-serving, and performance-payed management, comprise a twin threat against research freedom.

This is a threat that is more serious than certain politicians’ inappropriate interference in individual cases, namely the recent political attack on named researchers which claims that they conduct identity politics ‘disguised as science’. What the public debate on the politicisation of universities should focus on is the ongoing marketization of the universities which is accelerating these developments.

Comments