Fake news fighter: Nation sponsored dis-information worries me

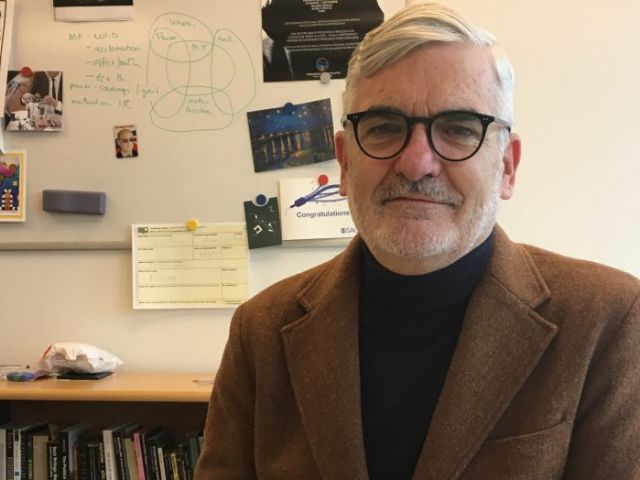

Together with four other global experts, Ravi Vatrapu is going to help creating a code of practice for the media and digital platform industry, in order to fight fake news. (Photo: Anne M. Lykkegaard)

The EU Commission has appointed CBS Professor, Ravi Vatrapu, along with four other global experts to advise on a code of practice on how to stop the spreading of fake news and disinformation. Ravi Vatrapu is confident about the future, but nation-state sponsored disinformation on social media worries him.

Ravi Vatrapu manages to squeeze an interview with me into his busy schedule. China awaits, nine PhD students, and four research projects need supervision, the Centre for Business Data Analytics needs to be run, and they are calling for him in Brussels.

The Professor of Computational Social Science at the Departments of Digitalization at CBS has recently been appointed by the EU Commission to be part of the Multistakeholder Forum on Disinformation and Fake News along with four other global experts. And they are meeting on the day he returns from China.

“Do I have free time for this? Not really. But it has to be done. I see it as a public service,” says Ravi Vatrapu and then laughs.

The aim of the forum, which also includes representative members from Facebook, Google, Twitter, and various other media associations, is to come up with a Code of Practice. In other words, a guideline which gives disinformation and fake news a hard time on the online platforms.

“Disinformation and fake news are not new. It has been around for decades. But what has changed everything is that now you have not only nation states that sponsor the production of fake news and disinformation, but also an ecosystem of political actors and vested interests to amplify it on social media platforms. That’s a whole other ball game,” says Ravi Vatrapu.

The EU-wide Code of Practice on Disinformation is expected to be published by July 2018, with the goal of having a measurable impact by October 2018.

“The Code of Practice is not a law, but a self-regulation initiative, which the different parts of the media and digital platform industry can sign voluntarily. However, if you don’t follow it, can you then call yourself a mediator of true information?” says Ravi Vatrapu.

Did Trump happen because of fake news?

Ravi Vatrapu came to be part of the forum, as he was invited to send in his CV to the EU Commission that then made the final decision on the five academics who will join the forum.

“This is an excellent opportunity for me, as a scientist, to have a high impact on an important topic at a societal level,” says Ravi Vatrapu about being part of the forum.

The CBS Professor will bring his expertise in computational social science combined with an in-depth knowledge on how to monitor social media to find fake news – especially in relation to elections.

Currently, one of his research projects investigates the impact of fake news on elections, such as the presidential election in the U.S. and Brexit.

“We have looked at one million links that were shared during the presidential election in the U.S. in 2016 on the official Facebook walls of Trump and Clinton. 10,000 of those one millions links could be categorized as fake news,” he says.

In the latest Eurobarometer survey, 83% of respondents said that fake news represents a danger to democracy. Respondents were particularly concerned by intentional disinformation aimed at influencing elections and immigration policies.

The best we can do is to give self-regulation a chance, and start monitoring what is going on out there

Ravi Vatrapu, CBS Professor

Ravi Vatrapu’s research, however, shows quite the opposite. Luckily.

“We need a more nuanced approach to disinformation and fake news’ impact on electoral outcomes. Did the election of Trump happen because of fake news? Did Great Britain leave the EU due to fake news? Currently, research is yet to show a significant impact from fake news on elections like these,” he says and continues:

“This is not to say that fake news didn’t play a role at all, but to say that it might not have been a major factor as we might believe. However, this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t monitor and regulate it.”

Ravi wants a fake news observatory

One way to get a more nuanced approach to disinformation and fake news is, according to Ravi Vatrapu, by monitoring what is actually going on out there. He points out that it is really hard to determine how many articles and links being shared in Denmark during the past month are related to fake news and disinformation, since no one is scientifically monitoring it.

“Currently, some of my colleagues and I are working on a proposal for a fake news observatory in Denmark. The observatory should be open to everyone so that we can see what is actually going on, and how big of a problem it is here. That includes researchers, journalists, politicians, and citizens, who could also be from outside of Denmark,” he says.

Ravi Vatrapu mentions that within academia there is actually a website, Retraction Watch, which informs researchers, journalists, politicians, and other people who are interested in the scientific articles that have been retracted from journals due to research fraud or severe errors.

Ravi Vatrapu wishes that there would be something like that for news, so that people could check which news and links have been categorized as disinformation and fake news. Until then;

“The best we can do is to give self-regulation a chance, and start monitoring what is going on out there,” says Ravi Vatrapu.

Comments