“I saw first-hand the mountain of fruit and vegetables discarded by the general markets… it was shocking!”

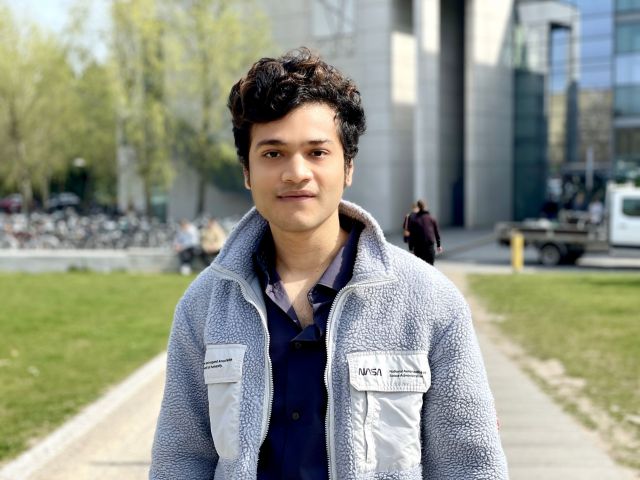

Cristiana Parisi is an Associate Professor at CBS. She is leading the Reflow Project, which aims to create circular and sustainable cities. (Photo By Anna Holte)

Reflow, the largest EU coordinated CBS project ever approved, is ending, but for the project’s main architect and coordinator Associate Professor in Management Control at CBS Cristiana Parisi, this is just the beginning. Reflow’s small green interventions give citizens the drive to do more. The project included three-year pilot projects in the cities of Vejle, Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris, Milan and Cluj-Napoca, and focused on recycling and reusing waste.

Cristiana Parisi has a bad cold.

Her voice is muffled and she has to catch her breath between sentences during the interview. But after managing a large EC project with 28 partners for three years, including keeping it running during the COVID crisis, it will take more than a cold to stop her. Reflow is the biggest project of its kind in the history of CBS, and her dedication and pride in the results shine through.

Despite being sick and tired, she has gained energy from the project, which has given her an unusual head start as an associate professor.

“A major project like this is usually carried out by someone more established, so that put me in the spotlight, which I liked though. Because of this project, I am now recognized within my field of research and all the positive feedback has also given me a lot of energy,” says Cristiana Parisi and continues:

“But, sadly, I think some people are provoked because I, an associate professor and a woman, managed to win such a large grant from the European Union and then successfully led and managed the partnership.”

Baby steps can accelerate big changes

The Reflow project focused on how a circular economy can help solve major waste problems in Europe. The project, which had 28 partners in 10 countries and 6 pilot projects in Vejle, Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris, Milan and Cluj-Napoca, received €10 million in funding from the European Commission and started in June 2019. Each pilot was based on solutions to waste problems highlighted by the cities themselves.

The idea behind Reflow is not so much to invent new solutions, but to provide guidelines and inspiration such as business model and plans, technology, governance, and social impacts, that can make a business sustainable both economically and environmentally, even after the project ends. These guidelines are designed to be easy to implement and adjust to local needs.

Reflow brings small green interventions and a system that allows small ideas to scale up

Cristiana Parisi, Associate Professor at CBS

Therefore, Reflow has measured and observed what the invested funds have meant for those involved in the pilot projects. Proving that Reflow is a good investment is in itself a selling point, besides being environmentally sustainable.

“Amsterdam featured a pilot project on textiles and one business model used featured second-hand clothes swap shops that prioritized hiring long-term unemployed staff, such as immigrants, people with health issues, or those on the sidelines of society. The idea is that sometimes doing something for the environment can also generate a social return as well as successfully building up their competence and confidence, and enabling them to find work elsewhere afterwards,” says Cristiana Parisi.

To her, the project success reflected a true drive to make a long-term change by involving citizens and proving that they can make a difference.

“One frequent question during the project involved agency and how much power to make interventions for change an individual can be expected to have. Especially since we are presented with cheaper alternatives to recycling every day. Of course, we are not blind to the fact that changing the growth paradigm will not be achieved any day soon,” says Cristiana Parisi and continues:

“In that way, Reflow was really visionary and clearly the European Commission recognized that. We allowed people to be creative, to rethink technology and materials, and find their own way to recycle and reuse, and through that take back some agency. Sometimes starting out with small interventions makes sense because then people buy into them as their own ideas and then perhaps begin thinking on a different scale. That can lead to real change and transitioning to a circular economy.”

COVID demonstrated Reflow’s flexibility

Making small ideas work on a grand scale became a very useful trait when COVID-19 hit in spring 2020. Many EU-funded research projects had the opportunity to go on hiatus or close down before time, but although Reflow was hard hit, the project continued, and the pilot cities found new ways of making recycling an asset in the fight against the consequences of COVID.

“In Amsterdam, the swap shops suddenly began receiving fewer clothes as the inner-city locked down, so instead, a side project worked on making reusable PPE for front-line hospital workers. The pilot project based in Milan worked on minimizing food waste by using scrap bread in the production of beer, for example. But with so many people struggling when COVID hit, they also redistributed discarded fruit and vegetables,” says Cristiana Parisi.

These additions to the pilot projects revealed how the original idea and theory behind Reflow transformed from being a linear methodology into flexible guidelines through feedback and learning on both sides.

“We soon learned that different cities had different interests and timing during the project. So even though every element of Reflow has been implemented in each pilot project city, they made and personalized their own mix based on their interests and the size of the city or project. So, we have learned a lot from the feedback from the cities and have adapted our methodology and the project along the way,” says Cristiana Parisi.

The open-source technology made available to the project, digital ledger technology (Reflow OS), supports this flexibility.

Facing and changing realities

Looking back, Cristiana Parisi really appreciates the teamwork and support from her partners, the European Commission and CBS surrounding Reflow and she was positively surprised by the resilience of the pilot cities and the enthusiasm everyone invested in the project.

“They were the driving force, they made requests rather than waiting for instructions, they proposed ideas, and when COVID hit, they suggested alternative activities to avoid stopping the project. They were the ones who said we can change things, we can put things online, we can use different tools, and their passion really inspired me,” says Cristiana Parisi.

For instance, the project in Milan focused on the enormous food waste from produce discarded before being sold to supermarkets all over northern Europe.

“I saw first-hand the mountain of fruit and vegetables discarded by the general markets. It was shocking to see. Tons of perfectly fine food and vegetables were being thrown away simply because they were slightly discolored and you wouldn’t even notice it,” says Cristiana Parisi.

For the venders, the prices are so low that they would just discard leftover produce, as there was no system in place for donations or making sure the produce could be used elsewhere. So, one Reflow project organized fruit baskets, QR codes and volunteers to redistribute what was donated throughout the day.

“Venders can easily use the system, and the quantities donated highlighted to the venders how much food they actually waste simply because they mostly operate business to business where strict regulations cover how food is handled. It made a huge change and benefited many people. Tons of fruit and vegetables are saved every day with this relatively simple technology,” says Cristiana Parisi.

Tons of fruit and vegetables are saved every day with this relatively simple technology

Cristiana Parisi, Associate Professor at CBS

She expects such small interventions, combined with user-friendly technology, can be used in other fields and she is pleased that the project in Milan and basically all the Reflow projects will continue to operate. In fact, new funding may be requested to see how much further the projects can go.

“We feel we are just getting started and are finally running like clockwork, and three years is not enough. We have received so much positive feedback from our partners and the European Commission that maybe there will be a Reflow 2.0. I feel like this is just the beginning,” says Cristiana Parisi, who has also been invited to work on other projects and collaborate with other universities.

Get the knowledge out there

In May, Reflow will publish its final reports and recommend some updated guidelines based on the experiences from the three-year project. Cristiana Parisi’s main goal is for the project to inspire other cities and citizens to take action and embrace the circular economy. And she is already being approached by universities that are considering replicating Reflow or requesting funding for similar research projects. She has found managing a project like Reflow extremely interesting, as it has not just involved observing cases, but also taking part in making a change.

“I really hope this practice will become more widespread – with universities actually leaving their ivory towers and reevaluate the old ideas of what universities should be doing. While rigorous research is fundamental, and REFLOW has already produced good publications, I also believe that universities should create culture. But they shouldn’t be elitist and produce knowledge that is read by friends and the 15 other professors in the field that attend every conference,” says Cristiana Parisi and concludes:

“Research like Reflow should also be used to improve living conditions in cities. I really feel that in my heart and it is an aspect I would love to continue working on. It is actually what drives me, and to be honest, I really believe it is more fulfilling not only as a researcher but also as human being.”

Comments