Fewer women than men apply for research grants: “They have a moral duty to do so,” says professor

Professor Eva Boxenbaum from the Department of Organization received a grant from FSE in 2013. Getting the grant meant a great deal to her and her career. (Photo: Anne M. Lykkegaard & Mette Koors)

The Independent Research Fund Denmark receives about a third fewer grant applications from women compared to men. At CBS, it’s even worse. The Vice Dean of Research at CBS argues that female scholars miss out on chances for promotion when not applying and thereby a possibility to bridge the huge gender gap at professor level.

Two grants from the Independent Research Fund Denmark|Social Sciences Council (FSE) played a significant role for Professor MSO Larissa Rabbiosi and Professor Eva Boxenbaum from CBS. The grants were part of making it possible for them to be promoted to their current positions.

“Getting funds as the principal investigator of a project is something you need in order to move forward in your career, as there are certain skills you need to learn before you can become a full professor. And for me, the grant I got in 2013 allowed me to progress career-wise,” says Eva Boxenbaum from the Department of Organization.

She received DKK 4.5 million to conduct the research project, ‘The impact of material artifacts and visual representation on the institutionalization of innovations’. The project made it possible for her and three other international female scholars to consolidate a new field of research.

When Larissa Rabbiosi from the Department of Strategy and Innovation got her grant in 2015, she was an Associate Professor. Now she’s a Professor MSO; the step before a full professorship.

“Without this project, I’m sure I would have had a tougher time becoming Professor MSO,” she says. Larissa Rabbiosi received DKK 2.2 million for her project, ‘The role of diaspora investors in developing countries: A study of firm internationalization and inter-firm collaboration.’

Figures show, however, that not enough female scholars apply for grants. In the period 2014 – 2018, 1,012 men applied for grants at FSE, compared to 674 women across all of the Danish universities. That’s a difference of 33 percent. At CBS, the figures are worse. In the same period of time, 90 men applied for grants at FSE compared to 56 women. That’s a difference of 37 percent.

And that’s a problem, says Nanna Mik-Meyer, Vice Dean of Research at CBS.

“If fewer apply, fewer will get funded. That’s one thing. Another thing is that getting external grants is an important factor for promotion. So when women don’t apply, and don’t get the funds, they’re making the run for promotion more difficult. Furthermore, there’s a lot of talent not being used. And that’s bad business,” she says and explains that when you’ve been funded once, it’s easier to get funded again.

“The winner takes it all, so to speak,” she adds.

Søren Serritzlew, Professor at the University of Aarhus and President of the Social Science Council at DFF, agrees that the imbalance is a problem.

“At DFF, we want to fund excellent research. We get a lot of high-quality applications, but between 2014 and 2018 we got 338 fewer applications from women than from men. When don’t get the applications, we can’t fund them, and this means we are missing out on talent and excellent research projects that never come to into being. And that’s a problem. Not only for us, but also for the women career-wise, as it is important to apply for and get funding,” he says.

Why aren’t they applying?

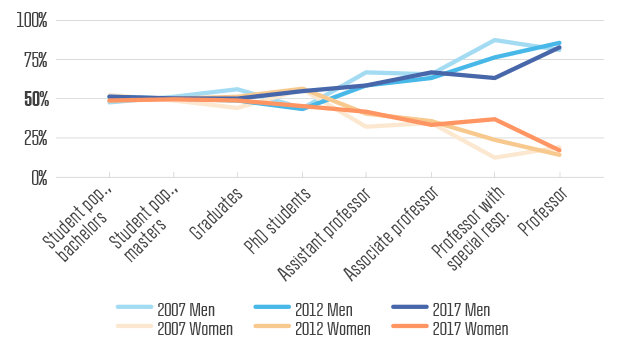

One thing that might explain the lower number of applications from female scholars nationwide and at CBS is the gender imbalance in academia, which is referred to as ‘the scissors’ at CBS.

There’s more or less a 50/50 share between men and women when they’re accepted to CBS, but when they pursue an academic career, something changes. The graphs of men and women part from each other as they climb the academic ladder and form a scissor-like shape. At professor level, there are currently about 80 percent men and 20 percent women. This pattern means the pool of women who can apply is much smaller compared to men.

Nanna Mik-Meyer thinks that when you have a smaller pool of applicants and an even smaller pool of women who receive grants, you get a shortage of role models. And according to her, role models are important for getting more applications.

“Depending on what field of research you work in, some women may think that the success rate is so small that it’s not even worth applying. This is why role models are so important so that the width of the projects that get funded is clear, and that it’s possible. No matter whether you’re doing research within social sciences or economics,” she says.

Søren Serritzlew agrees that the application rate is a reflection of the gender imbalance in academia. But in places where the balance is more equal, he doesn’t quite understand why women aren’t applying as much as men.

“I would like to encourage everyone to consider applying, as it’s quite attractive to apply for funding through FSE,” he says.

Women have a moral duty to climb the ladder

Larissa Rabbiosi had applied for and received other grants for research projects, but not as a principal investigator, before applying for the one at DFF. She thinks that some women want to be 100 percent sure that they actually have a chance of getting the funding before even applying.

“I don’t have evidence of this, but it seems that we want to be 100 percent sure about the project, and about whether we actually deserve the grant. And then I think because we lack self-confidence we are less pushy than men, both when it comes to applying for funds and getting a promotion,” she says and reflects:

“Moreover, there might be a time aspect in this. Maybe it’s harder or more challenging for women to juggle personal life and work and thereby finding time to do an application and run a project,” she says.

Eva Boxenbaum agrees that there’s a difference between men and women when it comes to applying for the funds, and this might explain the lower number of applications from women.

“Men are generally comfortable being in charge, and that’s somehow not as appealing to all women. We set up networks and collaboration and distribute the work and responsibility. When you’re a principal investigator, you supposedly have all of the responsibility for the project. But why does it have to be like that? This hierarchical structure might prevent some women from applying,” she says.

For her it’s crucial that women apply, especially if they want to change the gender imbalance in academia.

“To advance career-wise, we need to demonstrate that we have the required skills. So we have a moral duty to apply and put ourselves in a position where we can not only learn the skills needed to be promoted, but also demonstrate that we possess them. We need more women to climb the ladder, and getting research grants is one way of doing it. And it doesn’t help if we don’t take the opportunities that we’re offered,” she says.

CBS faculty should apply every second year

When Nanna Mik-Meyer was notified by FSE that there was a shortage of female applicants, she emailed the funding coordinators at every department at CBS and made them aware of the imbalance. And then she asked them to encourage everyone, but especially the female scholars to apply for grants.

We need more women to climb the ladder, and getting research grants is one way of doing it

Eva Boxenbaum

“In general, we want to have more success with our applications for both genders. So if we have talented women and men who don’t apply at all, they should be encouraged to do so. In that sense, I hope that the total number of applications will go up and that that number will include more women,” she says.

But what’s the goal? When are the figures good enough?

“I don’t think it can become 50/50 right away as you have research fields with a heavy gender imbalance, but it could be a goal to ask all staff at CBS to apply regularly,” she says.

For Larissa Rabbiosi it made a big difference that she was encouraged to apply by colleagues and senior scholars. That gave her the last push.

“The senior colleagues in my department are experienced people whom I admire and trust. So when they encouraged me to apply, that increased self-confidence and the perception that I could make it,” she says and explains that she’d rather have encouragement from colleagues than the senior management of CBS.

Set the agenda

When FSE receives the applications, it’s a team of different scholars with different academic backgrounds and genders who read through the applications and choose who gets the grants and who doesn’t. But what can FSE do to increase the applications rate for women?

“We invite the deans and vice deans from the Danish universities for an annual discussion about various topics, and this is one of the things that we’ll discuss with them. We would be happy to see more female scholars apply for funding, so we want to encourage the deans to thake this up at their faculties and departments,” says Søren Serritzlew.

Larissa Rabbiosi doesn’t see any obvious barriers from either CBS or DFF that would keep women in particular from applying. But CBS could do more to protect the scholars who are in the phase of writing an application or starting up a research project.

“It can be hard to find the time to write applications. So if a colleague appears to have a gem, CBS should help the scholars finding the time to write the applications,” she says.

Eva Boxenbaum agrees:

“You need to protect yourself from other tasks. I decided what I wanted to take up my time, and getting a research grant made it easier for me to turn down other tasks. Otherwise other people will fill up your time. So make sure that you set your own agenda – both in terms of writing the application, and when it comes to the research you want to do,” she says.

Comments