Why humour gets Danes into trouble

Lita Lundquist, professor emeritus at CBS and Helen Dyrbye, Copenhagen-based British freelance writer, have investigated why humour gets Danes into trouble. (Private photo)

A new book by two CBS-affiliated authors examines why the Danish sense of humour does not always go down well with foreigners who often consider Danes blunt and impolite. Much of the answer lies in the particularities of society and language.

A French scientist working in Denmark was struggling with the local language. When a local colleague casually suggested that he should divorce his wife and marry a Danish woman to improve his chances of mastering the language, the Frenchman took severe offence.

“It came up very coldly in a discussion, and as it was at a moment when I was trying desperately to learn Danish, it was very hurtful,” he later explained to one of the authors of a new e-book on Danish humour, written jointly by a Danish professor emeritus from CBS and a Copenhagen-based British freelance writer, translator and CBS language consultant.

But the hapless Frenchman need not have taken the remark so seriously. Had he been more familiar with Danish mentality, he might even have dismissed it as a perhaps crude, but fairly innocent, bit of humour. On the other hand, had his Danish counterpart realised that non-Danes do not necessarily understand that kind of humour, he might have shown more restraint.

Insight and warnings

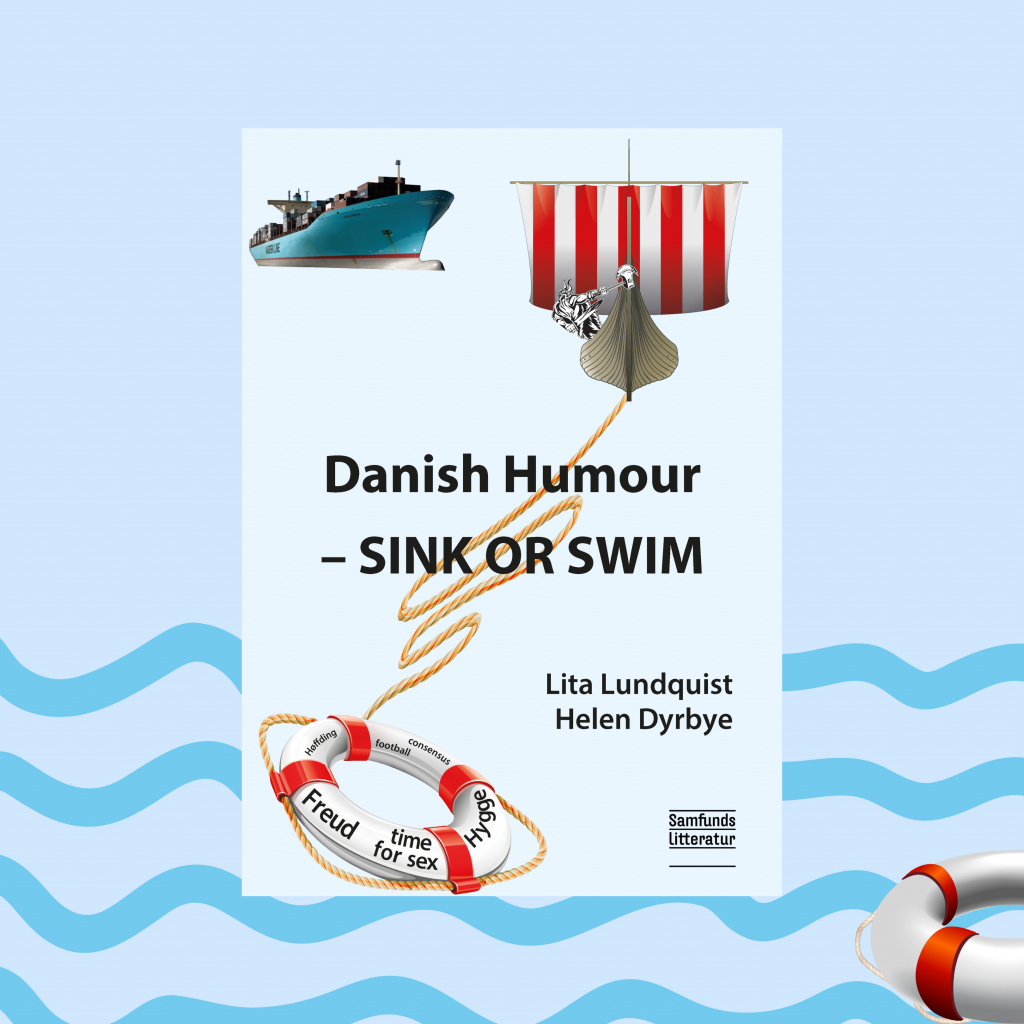

“Danish Humour: Sink or Swim” has been written with such awkward situations in mind. Offering useful advice to Danes and non-Danes alike, authors Lita Lundquist and Helen Dyrbye hope that their book can fulfil its double goal: “firstly, to provide insight and warnings to a wide range of Danes, and, secondly, to help all other nationalities to open up and accept the friendly intention underlying what can come across as ‘sledgehammer icebreakers’.”

We have this campfire mentality which means that we sit together and say things directly

The latter expression refers to situations where Danes use humour to break the ice with a foreign counterpart and instead end up shocking them. Lundquist and Dyrbye have described and analysed numerous incidents involving Danes and foreigners. Their book combines academic research and often amusing observations and is primarily aimed at Danes and non-Danes who work, study, or do business together.

Two years ago, Lita Lundquist published a book in Danish with the title: “Humour Socialisation – Why Danes are not as funny as they think they are”. The book was based on research that included interviews with 26 CBS students from 14 different countries, together with interviews with Danish, French and German Members of the European Parliament and Danish businesspeople working in France, and vice versa.

In this book, Lundquist introduced the concept of humour socialisation as a way of explaining a particular ‘national sense’ of humour. This means that Danes, like other nationalities, have developed their particular sense of humour from growing up in a specific social context and with a specific national language.

A humorous approach

Lundquist was encouraged to make an English version of the book, which is how British-born Helen Dyrbye came on board. But what should originally just have been a translation turned into something different as Dyrbye was able to add her own experiences as a foreigner living in Denmark – and adopt a more humorous approach than would normally be the case in academic work.

“We wanted it to have a more general appeal, so we turned it into ‘academic light’,” says Helen Dyrbye, who had previously been involved in writing a humorous account of life in Denmark – The Xenophobe’s Guide to the Danes. The result is a book that strives to be informative as well as entertaining.

A key to explaining Danish humour is the ‘campfire mentality’. When Danes gather around a large, communal bonfire – metaphorically speaking as well as in real life – they are seated at the same level and feel secure in each other’s company. Hence, they use irony and self-irony without any fear of making fools of themselves – and they assume that their foreign counterparts understand their humour.

Alcohol and sex

In such situations things can go wrong as in the case of the French scientist. In another clash between Danish humour and a bewildered foreigner, a young Chinese student, excited to meet a Danish CBS classmate for the first time, initiated their conversation with the following remark: “I have heard that Danes are the happiest people in the world,” he said. The response from his Danish fellow student was as prompt as it was unexpected: “That’s because of excessive use of alcohol and sex.”

The Chinese student was stunned, felt somewhat offended, and later described his reaction as follows: “I was very surprised. I would have preferred a more discreet and restrained form of humour. (…) Maybe because I am from a country with a tradition for censorship and reserve.”

We are trying to help non-Danes cope with Danish humour and see it as an invitation to play

None of the Danish counterparts to the French scientist and Chinese students intended to offend them. On the contrary, they probably wanted to be inclusive. However, they failed to understand that this kind of humour is not necessarily accepted in other cultures. The authors make the following plea to non-Danes who end up in similar situations.

“We would urge non-Danes to try not to be offended and instead stretch a good long way and do everything they can to find good-natured meaning and relevance in what Danes have to say – while trying not to register any visible signs of shock.”

Von Trier and Hitler

Such a plea would probably have failed to make an impact at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival when Danish film director Lars von Trier – until then a festival darling – caused outrage when jokingly describing himself as a Nazi and expressing a certain sympathy for Hitler. For this display of extremely poor taste, he was subsequently banned from the festival.

Lundquist and Dyrbye admit that they do not necessarily understand the director’s complex personality, nor can he be said to be an average Dane. Nevertheless, they believe that the embarrassing incident shows “some characteristics of how Danes like using humorous remarks to skate dangerously close to taboo topics.”

Von Trier failed to convey that he was not being serious for a number of reasons. He forgot that he was a Dane speaking to an international audience, he was being ‘self-ironic’, and he had not mastered the subtle nuances of the English language.

Language is an important element in humour socialisation. The book argues that had von Trier spoken in Danish, he would have been able to soften the impact of his remarks by inserting the tiny word ‘jo’ into some of his sentences. And of course, the authors state with a glint in their eyes, “this book might have provided him with a welcome lifeline.”

Repairing the damage

Both authors hope that their book will have a positive impact and make humorous interactions between Danes and non-Danes easier.

As Lita Lundquist puts it: “We hope to make foreigners understand that we do not intend to offend anyone. We have this campfire mentality which means that we sit together and say things directly. We hope that the book may contribute to improving international professional relations so that we avoid awkward situations as in the European Parliament where Danish MEPs sometimes need to run around and repair the damage if they have been too blunt.”

Helen Dyrbye, who herself struggled to get to grips with the Danish sense of humour during her early years here, stresses that the authors do not wish to tell the Danes off: “We are trying to help non-Danes cope with Danish humour and see it as an invitation to play. We would like people to feel happier about using humour on more stable ground.”

Dear D D

You are perfectly right! And we cover exactly that aspect and many more in our book!

Thanks for your comment,

Lita and Helen

I think there’s also an element of having a set of friends with far more similar backgrounds than most internationals. Many Danes I’ve met have not thought extensively about the perception of the jokes that they are telling on those with different backgrounds nor have they experienced/witnessed the harm that some of these jokes convey in people’s real day-to-day life. Many people see it as a joke because they could or have never seen it. I know many Danes that don’t know anyone that is Jewish and as is such a biting joke about the holocaust may seem funnier than it actually is.