They turn old negatives from an Atlantic expedition into digital art by using blockchain software

It was his interest in digital art that brought Sebastian Tiku Lybecker to CBS to enrol in a course on ‘blockchain and sustainable digital infrastructures’, and his recently acquired knowledge about this technology prompted him to join forces with photographer Marc Fluri in an extraordinary art project. (Photo by Kim Wiesener)

A CBS student is one of the driving forces behind an unusual project that is transforming old negatives from the 1920s into digital art. And if the NFT pictures sell out, they will start looking for more old negatives that tell a good story.

When the three-masted schooner Blossom travelled the Atlantic Ocean in the 1920s, exploring exotic locations in Africa and South America, its crew members could hardly have imagined that the photographic records of their expedition would become the focal point of an art project almost 100 years later.

Had anyone tried to explain to them what the project entailed, they would have dismissed it as pure science fiction. Indeed, the technological gap between the fragile, faded negatives that still exist as memories of ‘the Blossom Expedition’ and today’s digital space is almost unimaginable. Nevertheless, it has been bridged by three Danes who decided to join forces and introduce a way of making art that is quite unusual in Denmark.

On Thursday 24 March, the virtual ‘Blossom NFT Expedition’ will be launched. Describing itself as “a voyage into the new world of digital art”, the project will issue the first series of ‘non-fungible tokens’ (NFTs) based on carefully restored versions of the 99-year-old celluloid negatives from the real-life scientific expedition that took place from 1923–1926.

An NFT is a unit of data that is stored on a so-called blockchain, a system of recording digital information in a way that makes it very difficult to change, hack or copy. Blockchains are probably best known as a platform for crypto currencies, such as bitcoins.

NFTs guarantee ownership of the digital piece, whether a photograph, video file or another digital item. They are increasingly being used in the art world, in fact some NFTs – also known as crypto art – have sold for tens of millions of dollars. This has also created controversy, as some critics question whether crypto art has lasting cultural significance.

It was his interest in digital art that brought Sebastian Tiku Lybecker to CBS to enrol in a course on ‘blockchain and sustainable digital infrastructures’, and his recently acquired knowledge about this technology prompted him to join forces with photographer Marc Fluri in an extraordinary art project.

Shopping for old negatives

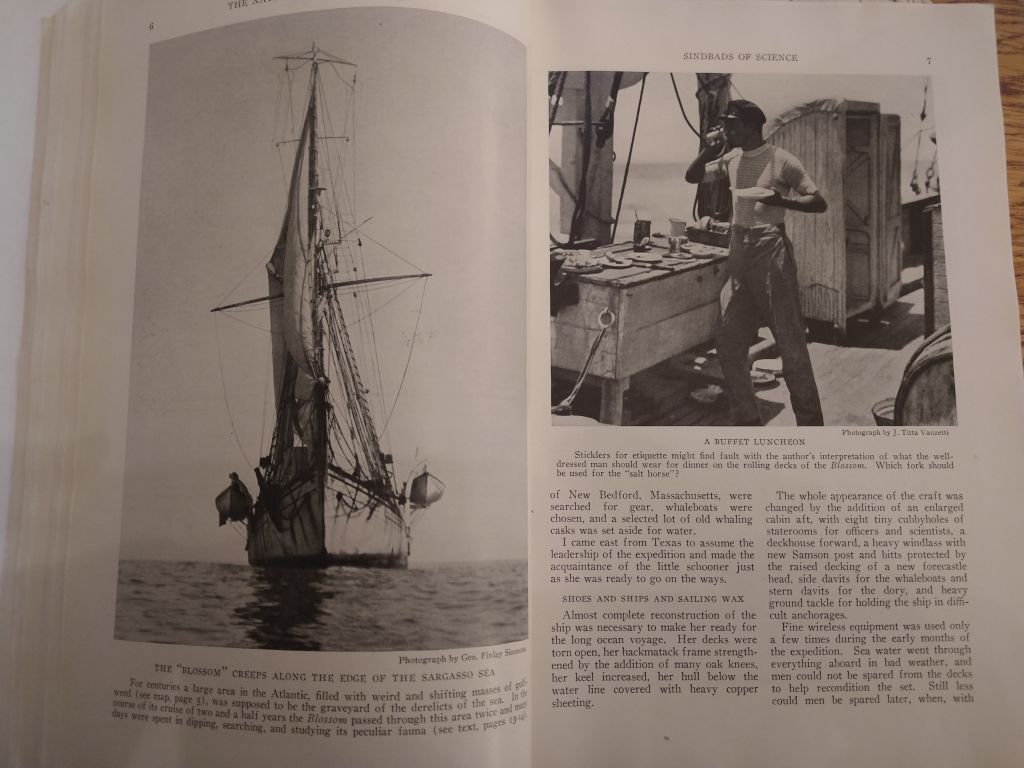

Fluri had been shopping around at auctions for years acquiring old negatives, and among his favourite acquisitions were approximately 350 surviving negatives of the many thousands taken during the Blossom Expedition.

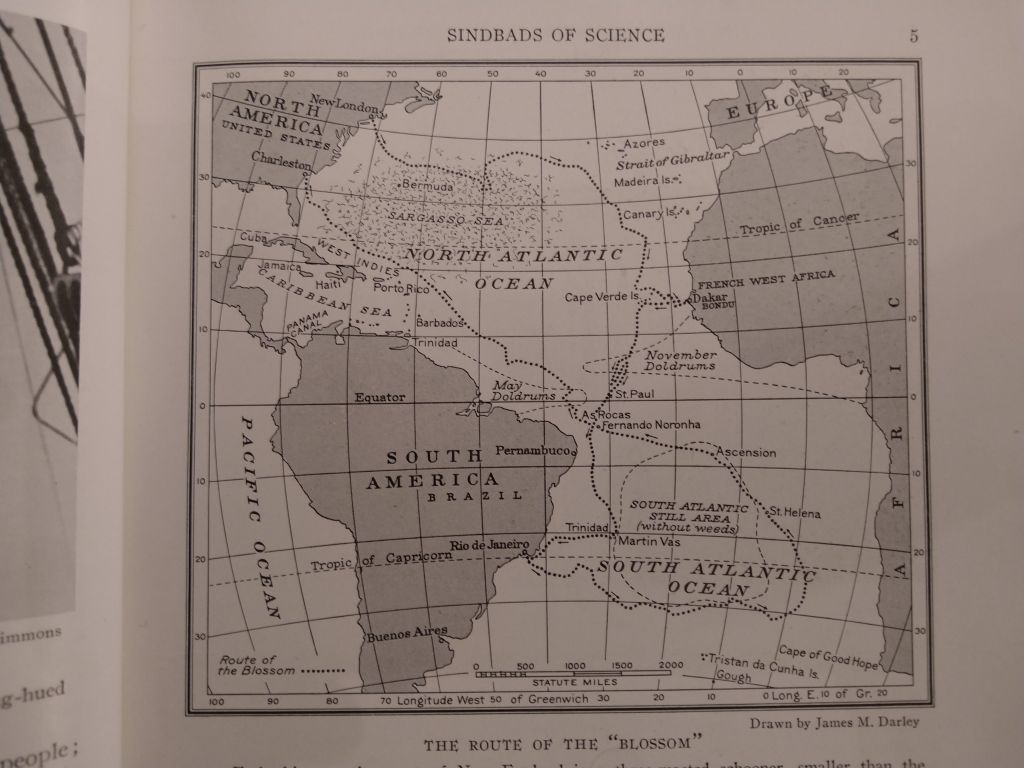

This scientific venture – also known as the Cleveland Museum South Atlantic Expedition – set out from Connecticut, USA, in October 1923. Its main mission was to study and collect the birds of Africa, South America, and the islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. The schooner was equipped with an onboard darkroom and state-of-the-art photographic equipment.

The Blossom Expedition made numerous stops in places such as Cape Verde, Senegal, Rio de Janeiro, Ascension Island and St Helena, and eventually returned to the US in June 1926. By then, the ship had been travelling for two years and seven months and had covered approximately 35,000 kilometres. Some of the original crew did not return as they fell in love with local women during the journey.

On the way, the expedition collected 13,000 specimens of animals, including 5,000 birds, as well as lots of scientific data. The expedition’s exploits were described in detail by the National Geographic magazine in 1927, and its members were dubbed the Sindbads of Science – a reference to the adventurous seafarer from One Thousand and One Nights.

(Photo by Kim Wiesener)

Memories of the expedition faded over time. But the explorers also took thousands of photographs, many of which have since disappeared. However, those that still exist tell a fascinating story about adventures, mishaps, and exotic locations.

Preserving the records

Marc Fluri’s decision to buy all the negatives he could find from the Blossom Expedition was also based on the following knowledge: old negatives do not last forever. The best way to save the surviving photographic records of the expedition from gradually self-destructing was to preserve them in some kind of digital form.

Thus, the idea of making digital art out of the negatives was born. Fluri, Lybecker and the third project member, Jesper Munk, decided to conduct an experiment – they would transform some of the photographs from the expedition into NFTs, turning something that was never thought of as artistic into unique digital art objects.

(Photo by Kim Wiesener)

They founded a company called EyeEye with the purpose of offering original historic images as NFTs, and hence, the ‘Blossom NFT Expedition’ came into being. In a few days, the first 25 of 99 NFTs will be ‘minted’ – created on the Cardano blockchain – and put up for sale. Later this year, three more series will be issued. The NFT acts as a kind of certificate that gives the buyer ownership of a unique piece of digital art that can only be viewed on a screen.

Originally somewhat dismissive of crypto art, which some critics consider an easy way of making money – Sebastian Tiku Lybecker describes the project with an almost contagious enthusiasm. He is obviously fascinated with the story behind the photographs, which, in his opinion, is part of our shared cultural heritage.

Having studied blockchain technology at CBS – and been encouraged by his teachers to use it actively – he is also eager to show CBS students one potential outcome of such a course.

Crypto currency

The NFTs can only be paid for with crypto currency. Lybecker lists a number of reasons to buy the Blossom NFTs. You are acquiring a unique piece of global cultural history; the beautiful photographs represent an aesthetic value; the project is the first of its kind in Denmark; and the technology used definitely points towards the future.

“It is also important to remember that if we don’t do this, the negatives will disappear. Their life span is running out, many of them are already damaged. We can’t leave it to museums to preserve them, as they are under severe financial pressure. In that sense, private collectors are more reliable when it comes to preserving our cultural heritage,” Lybecker points out.

Potential customers in the increasing market for NFTs could include well-educated males in their twenties and thirties who have taken to the phenomenon as a means of owning and ‘showing off’ digital art – on their computer screens, smartphones or bespoke NFT screens.

“We don’t know whether the project will be a commercial success, but we do hope to make some money from it, while also providing our customers with a unique piece of history,” he adds.

If the Blossom NFTs are successful – and perhaps even sell out – the three partners aim to continue their digital art project. It will be with different motives than those featured in the Blossom Expedition, but historic negatives will once again be the starting point. In that case, Marc Fluri may soon be back in an auction room – virtual or real – looking for old negatives that tell a good story.

(Photo by Kim Wiesener)

Comments