International scientific publishers milk universities – you and I pay the price

René Steffensen, Director of Campus Services and Library at CBS has had it with the international publishers' pricing. (Photo: Private)

International scientific publishers have profit margins that rival Google and Apple. Universities are struggling to disentangle themselves from the system, which has created a state of dependence. “It’s daylight robbery,” says CBS Director of Library and Campus Services. Does a new agreement with the Danish universities outline a way out?

Picture this: a farmer milks his cows and gives away the milk to the dairy company. Then he pays a high price to buy a carton of his own-produced milk back from the same dairy company.

Sounds like a bad deal, right?

In a nutshell, this is exactly the situation universities all over the world are in when publishing scientific articles in international journals.

Researchers conduct research that most often is paid by you and me – taxpayers. The researchers then write about their results and give them – for free – to international scientific publishers to publish in their journals. And here is the sting in the tail. Universities then pay millions for licenses to access their own research.

The price increase is exorbitant. And I would have said the same 10 years ago, which tells us nothing has changed

René Steffensen

A handful of international scientific publishers – Elsevier, Nature, Sage, Springer, Wiley and Taylor & Francis – are the top dogs, publishing about half of all scientific articles, and they earn tremendous amounts of money on research that they are offered for free.

For instance, Elsevier had a net income of DKK 21.8 billion in 2019. In fact, Elsevier’s profit margin that year was 37%. That is more than Google, Amazon and Apple each presented the same year.

“It is deeply problematic that universities all over the world are in a situation where they are force to give away research to publishers in a complex and in many ways reasonable merit system whereby the publishers obviously capitalize on their monopoly,” says René Steffensen, Director of Library and Campus Services at CBS, and continues:

“But it’s especially the profit margin that makes me angry. If they had a profit margin of five to ten percent, it would be acceptable. But 37 is just absurd. Why can’t they just settle for one billion?”

The debate about the monopoly-like situation a handful of scientific publishers have created is not new, but reignited when, on behalf of the Danish universities and other research institutions, the Royal Library’s national licensing consortium agreed on a four-year contract with Elsevier worth DKK 295,872,960 in January.

In an opinion piece from February in the Danish newspaper Weekendavisen, Bertil F. Dorch, who is the Director of the Library at the University of Southern Denmark, and Professor Charlotte Wien criticized Elsevier – or ‘Evilzevier’, as they call the publisher.

“Elsevier deals with its suppliers and customers in a very high-handed manner: annual price increases of between 3–5% are normal. In comparison, retail prices increase by about 0.5% a year. Similarly, retail businesses are doing well if their profit margin is 5–6%. Elsevier’s profit margin is 37%,” they write and add:

“For the record, it must be said that 70 percent of the business is public money, which could have been used on research.”

A new contract – a new direction?

Every year, the Danish research libraries pay about DKK 300 million for access to scientific journals and data bases. And about 80 million of that goes to Elsevier.

According to a press release from the Royal Library, the new contract with Elsevier is the first of its kind in Denmark to ensure full reading access to Elsevier’s journals, and free and immediate access, so-called Open Access, to the articles published by researchers at the institutions covered by the agreement.

The new agreement also covers CBS Library, which has undertaken to pay DKK 23,039,347 in total for the four-year deal, according to the contract between Elsevier and the national licenses consortium announced by the Royal Library. And the price could have been much higher, according to René Steffensen.

“The price for the entire period 2021 to 2024 is fixed, whereas we have experienced large annual price rises previously, and this has been crucial for CBS. We are not naïve and believe that it would have been hard for the Royal Library to get a better agreement right here, right now,” he says.

When asked, Jesper Langergaard, Director of Universities Denmark, says he too is satisfied with the new agreement, in which he has great confidence.

“We were really happy when the deal was signed, as it signals a change of direction. We entered the negotiations with demands for free and immediate access to publications and we were not prepared to accept price rises, and we succeeded on both counts. Hopefully, this agreement will signal to the other publishers what we want,” he says.

Has the limit been reached?

Annually, CBS spends about DKK 17 million on licenses and access to scientific journals, and due to strict confidentiality clauses in the contracts, René Steffensen is unable to disclose the prices paid to each of the major publishers – Elsevier, Sage, Springer, Taylor & Francis and Wiley – but reveals that between 2016 and 2020, CBS experienced a price increase of 14.6%.

“The price increase is exorbitant. And I would have said the same 10 years ago, which tells us nothing has changed,” he says.

On the question of whether he has experienced similar price increases within other areas, he says:

“I don’t believe I have seen anything similar to the price rises we have experienced from the publishers. Natural competition is common in most sectors today. If you were the only laptop manufacturer in the world, you would take a different price. And the publishers and private equity funds behind the publishers exploiting their monopolistic positions are ruthless.”

If you ask Jesper Langergaard whether the price limit is about to be reached he answers:

“It was reached and crossed a long time ago,” he says and continues:

“We are still stuck in this mechanism, and to be a little critical of ourselves, we have started to wake up and say stop. We have a function that we would be sad to live without, but we cannot live with it if the situation continues this way. So I’m happy that the tide seems to be turning, and I’m positive about future negotiations.”

In fact, the national licenses consortium was ready to leave the negotiations if the deal did not pan out as planned.

“If we hadn’t seen a change of direction during the negotiations, we would have walked away. And yes, that would have resulted in no access to publications for some time, but we were ready for that,” he says.

The need for publishers – a love-hate relationship

So how, exactly, did the universities get into a position where they spend millions on buying access to their own research?

There are several reasons – but why do universities even need publishers?

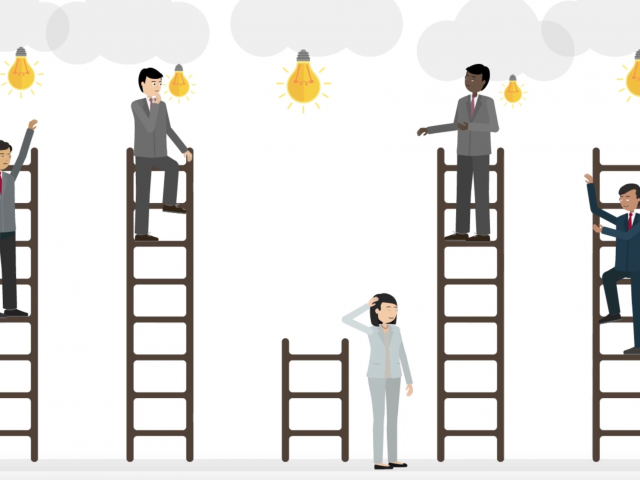

Researchers’ careers are largely based on the research they make. The better the research, the better the journals where a researcher can publish. So if you want to climb the academic ladder, your research must be published in the best journals within your field.

Moreover, university rankings are often based on how many top-tier articles a university produces. The rankings reflect the individual university’s excellence in research and can be used to attract world-class researchers.

Another aspect of publishing research in journals is the peer-reviewing process.

Before a scientific article is published, it passes through a peer review process whereby researchers from the same field review the scientific article checking the methods and results, and looking for any discrepancies in the work. This is intended to assure the quality of the research.

According to the Global State of Peer Review report from 2018, researchers spent 68.5 million hours reviewing each year between 2013 – 2017 for free. If, however, you multiply the number of hours spent reviewing by the Danish minimum wage (DKK 110 an hour) it would add up to DKK 7.5 billion that the researchers donate to the publishers – for free.

It’s daylight robbery

René Steffensen

A final aspect of this tight-knit situation is the monopoly held by some major publishers. They own journals that you cannot gain access to in other ways without paying a price. And when they have a monopoly, they set that price.

Consequently, university libraries around the world have no chance of ‘shopping’ around at different publishers for the lowest price when only one publisher can offer access to the research they need.

“Either you pay the price, or you have no access to the research. It’s as simple as that. And if you want to pay and the price keeps rising, eventually you must save money in other areas,” says René Steffensen.

Bring in the EU

As mentioned, this criticism of the scientific publishers is not new. In fact, in 2018, Universities Denmark initiated an open letter to Margrethe Vestager Commissioner for Competition in the European Commission, asking her to look into the concerns over the publishers’ monopoly. The letter was signed by about 850 European universities across 48 countries.

Back then, the Dean of Research, Søren Hvidkjær said about the letter and the situation:

“Researchers and universities pay at least twice for publications. Researchers pay submission fees and then universities pay subscription fees to electronically access the published articles. The fees are substantial, and this means that we have fewer funds available for other important activities,” he said.

At the time when the letter was sent to Margrethe Vestager, Jesper Langergaard said to Videnskab.dk:

“We believe we have the documentation in place to show that something is utterly wrong. Our dream is that Vestager will take up the case and make the major publishers act accordingly, like she has done with giants such as Facebook and Google,” he said back then to the Danish science media Videnskab.dk.

Jesper Langergaard is still hoping that the EU’s competition authorities will take up the matter.

“We are continuing to push for this, and we hope that the EU will investigate the publishers and whether they can be regulated, and hopefully reach an international solution,” he says.

So what might be a palatable solution?

“We need free access to everything and at a price that reflects the work researchers put into the publications and review processes,” says Jesper Langergaard.

René Steffensen also believes the authorities at EU level are the ones with the muscles required to deal with the situation, as the publishers have the universities over a barrel.

“This issue cannot be solved by CBS, the Minister or Denmark alone. It has to go to the EU, and they will have to regulate and legislate us out of the problem,” says René Steffensen, explaining that even cancelling the licenses would have no effect:

“The universities have but one weapon – to cancel the licenses. Let’s say we cancel the agreement with Elsevier, but after a year a year got a new, more reasonable deal and decided that we want back in. Then Elsevier would say that if we want to gain access to the past year’s publications, we have to pay. So no matter what, we will have to pay. It’s daylight robbery,” he says.

Comments