CBS’ Data Protection Officer calls an EU Court of Justice decision “one of the wildest in his field” and it has a major impact on researchers

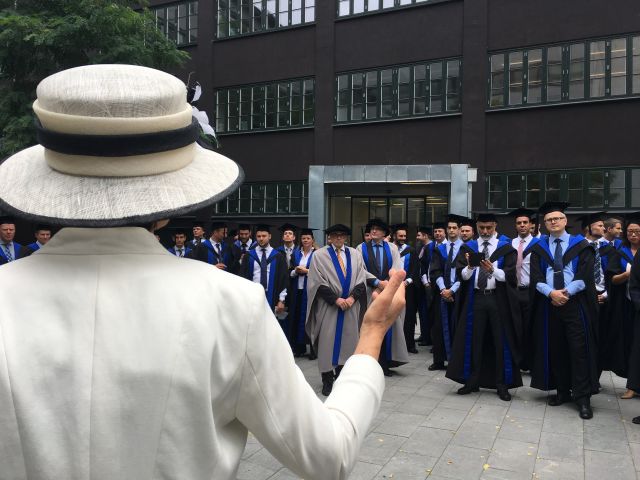

Jesper Smedegaard Madsen is CBS' Data Protection Officer and he explains how the so-called Schrems II case can potentially affect research and researchers going forward. (Photo: Lisbeth Holten)

It started as a quarrel between an Austrian activist and Facebook, now the decision in the so-called Schrems II case in the EU Court of Justice has consequences for researchers who cannot as easily share personal data with colleagues outside the EU. The question is: Can you strive for open access and adhere to strict data protection rules at the same time?

Maximilian Schrems is a 33-year-old Austrian data privacy activist. He has run campaigns against Facebook for its privacy violations, including violations of European privacy laws and the alleged transfer of personal data to the US National Security Agency (NSA). And the latest case he has won is now having consequences for EU researchers.

In July 2020, Maximilian Schrems won the so-called Schrems II case at Europe’s highest court, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). They ruled that a transatlantic agreement on transferring personal data between the EU and the US used by thousands of corporations did not protect EU citizens’ privacy. (See fact box)

So what does this mean for researchers? It means two things: researchers cannot as easily share personal data, both sensitive and regular, with partners and colleagues outside the EU, and that systems that are currently used might not comply with data protection legislation.

“The court believes that there is too much opaqueness in terms of what our personal data is used for and how it’s stored in countries that do not have the same level of data protection as the EU,” says Jesper Smedegaard Madsen, Data Protection Officer at CBS about the decision, which he calls “one of the wildest” in the past 10 years in his field.

“This decision will affect research a lot, as we use a wide range of systems provided by American suppliers, mostly, and this decision underlines that you are almost not permitted to transfer data to the US,” he says.

When we talk about personal data, it can be any data that can identify you. Phone numbers, CPR numbers, e-mail addresses, addresses, health data or other types of data. And what Maximilian Schrems wanted when he ran his campaigns against Facebook was to make sure that his data was not used without his permission. Whether it be by Facebook or businesses.

One example of how personal data in a research context can be exploited stems from the research institute Statens Serum Institut. In November 2020, Danish journalists at DR revealed that 172 pregnant Danish women who participated in a research project at Statens Serum Institut, had their blood samples shared with American researchers without their permission.

The researchers in America had received the blood samples from Statens Serum Institute and used the data to develop a blood test that can predict premature birth – a test that a research center established by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, and a private start-up company in California would profit from.

And now for the tricky part

Recently, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has shared a set of guidelines on what to do if you want to transfer personal data to a country outside the EU, as well as what to do if it is estimated that a country or business outside the EU cannot deliver the same level of data protection.

Jesper Smedegaard Madsen explains that what researchers can do is to pseudonymize the data.

“In many cases, it will be possible to replace the CPR number or an email address with a letter, number or some other kind of ‘key’, so that the data is protected. And this can be enough for permission to transfer the data out of the EU. And that is the easier part,” he says.

We need to discuss how research and GDPR can benefit each other, and I really hope that the EU is up for discussing this topic

Jesper Smedegaard Madsen

The other part of Schrems II is about how our data is stored and applied in the systems we use. For example, researchers use various systems for teaching and researching that store and analyze data. Systems that are indispensable and timesaving.

“In some cases, researchers receive help from people outside the EU when collecting and storing data for research purposes. In those cases, we need to make sure that the systems they use live up to the high standards of data protection,” he says and continues:

“But it is a little more complicated than that. Let’s say we use a system that is owned by an American company. The data is in the EU, but the support team is based in the US or some other country outside the EU. And this is a problem if the support team has access to the data. And that’s one of the major challenges and something most universities are struggling with.”

Jesper Smedegaard Madsen says that pseudonymizing the data would solve the problem, or making sure that the company does not have access to the data – in any way. So if the American government asks to access the data, the company must say that it cannot access the data, as someone else in the EU has the “key” to the data.

“In a Danish context, it would make sense that Statistics Denmark could be a key player in being in charge of the access to various kinds of data – like they are now,” he says.

However, as it is right now, the companies that deliver the services and systems used by researchers and universities are not geared to make the changes that the EU is calling for, says Jesper Smedegaard Madsen.

“Some suppliers have started to realize that being able to deliver data protection in compliance with EU standards can serve as a competitive advantage. They will have to change if they want to keep their customers, but that will not happen overnight,” he says.

A systematic approach

CBS is, according to Jesper Smedegaard Madsen, in a lucky position. Unlike universities such as the University of Copenhagen or Aarhus University, CBS does not conduct health science. We have access to health data but, as the research is primarily within social sciences and humanities, the data protection issues are easier to work with.

“When it comes to data, it’s a little easier. However, we have the exact same issues regarding the use of systems as other universities,” he says.

Already, CBS Procurement and Legal has made a visitation process for all new required systems, and IT and CBS Procurement are currently reviewing all CBS systems to check how personal data is stored in the systems and how the suppliers can help to ensure that data protection rules are kept, explains Jesper Smedegaard Madsen, who says most of 2021 will be spent on getting through the existing CBS’ systems.

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

But what happens if a supplier, a researcher or CBS does not respect the data protection rules?

“First of all, we all have a responsibility to make sure that CBS keeps to the rules. That being said, the individual researcher cannot get fined. CBS can, however. Secondly, we have not yet heard of any consequences of the Schrems II case, but it’s obvious that transferring personal data out of the EU will have consequences. However, it’s almost impossible to say anything about the level of sanctions,” he says.

A clash between GDPR and research?

Jesper Smedegaard Madsen says that although they have received guidelines from the European Data Protection Board, the guidelines leave room for interpretation and do not always answer issues properly.

“I think we will have to collaborate with universities outside the EU on transferring personal data. Yes, it can feel like a formality that slows down processes, but the Schrems II case shows that having these formalities in place is more important than ever,” he says.

Just as suppliers will have to change how they store the data, universities will also have to find ways to work with the new rules. Jesper Smedegaard Madsen hopes that Schrems II will be the boost needed to create a European infrastructure for transferring research data.

“This would make it much easier for researchers to store and share data. We are seeing some work on this, but not at a level one could wish for,” he says.

And talking about the EU, Jesper Smedegaard Madsen hopes that GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the Schrems cases will highlight the sometimes contradictory relation between research and data protection.

“In a research context, GDPR is a very rigid regime. On the one hand, the EU gives out billions of Euros to research and wants that research to be open and possible to share, but in many cases, that clashes with GDPR. So we need to discuss how research and GDPR can benefit each other, and I really hope that the EU is up for discussing this topic,” he says and adds:

“Research is not just European, it’s global.”

On April 30, The European Data Protection Board hosts an online meeting to consider a range of GDPR challenges in the context of research. Due to a limited number of spaces at the meeting, CBS cannot participate in the meeting, however, Peter de Fønss, from the University of Aarhus, will attend the meeting and share input from all of the DPOs at the Danish universities.

And just this month, Maximilian Schrems filed a complaint against Google in France alleging that the US tech giant is tracking Android phone users illegally because it does not have their consent.

Comments