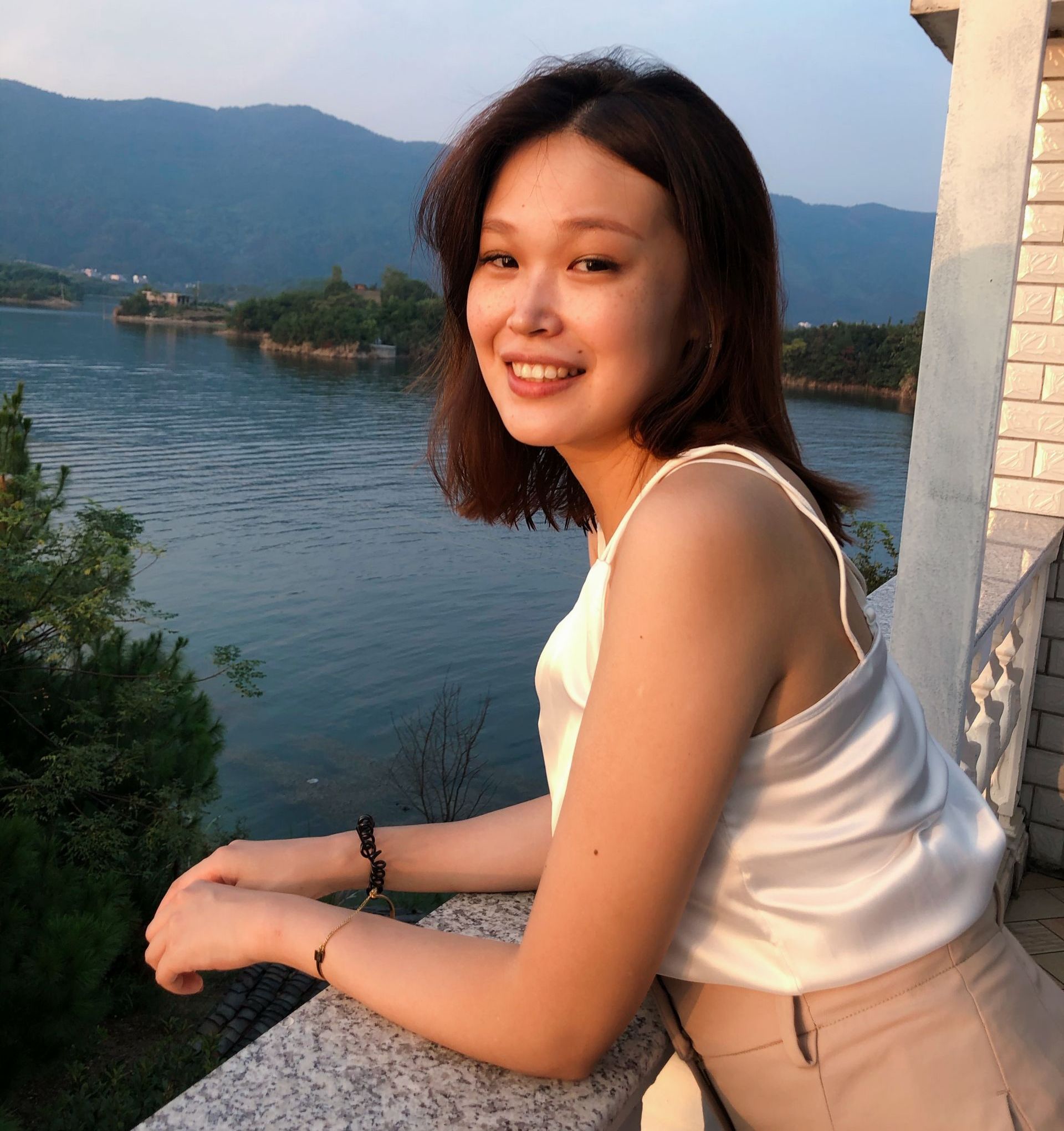

“My parents called me and said: ‘How dare you not wear a mask on the street?!’”

(Private photo: Xuan Li)

CBS Postdoc Xuan Li was cooped up in Wuhan with her family in an apartment on the 29th floor for three months. One year later, she once again found herself in lockdown – this time in Denmark. And although the restrictions are less rigid this time, she is still affected by her firsthand experiences of the pandemic.

In November 2019, Xuan Li traveled to her hometown Wuhan to reunite with her family, celebrate her new PhD title from the University of Copenhagen and celebrate the Chinese New Year in February. After that, she planned to go on vacation in Norway. That was when the world’s first and most rigid lockdown began.

“I was scared. In Wuhan, there was a clear dividing line between before and after the lockdown. Before that, the citizens weren’t well-informed by the health authorities, so it kind of took us by surprise,” she says.

It all began on January 23 last year when a curfew was imposed on Wuhan.

“My plane ticket to Oslo got cancelled, and for the following three months, I was locked up in the apartment with my family,” she says and continues:

“It was shocking how fast the virus suddenly gathered speed, and the government had to take serious measures to contain its transmission. Never before in human history had anyone heard of such a situation. So, at that time, I was really worried!”

And Xuan Li did have cause to worry. According to WHO, when the outbreak began there were about 1,500-2,000 cases of infection per day in China as a whole.

But the transmission quickly gained speed and on February 13, the number of cases increased by 14,840 on a single day in the Hubei-province alone, where Wuhan is located – a sudden increase that was due to new calculation methods.

The discussion can turn into hate, and hate transmits faster than any virus

“That was also when I read in the news about hospitals getting overloaded, and that even though the doctors and nurses were making a huge effort, they were under major pressure,” Xuan Li says.

However, in April 2020, Wuhan regained its hospital capacity and slowly began unlocking the city. Some people could return to work, and a selection of shops could reopen their doors.

But due to the risks of going out, Xuan Li stayed inside for a little longer. That was when she could read the debate about China’s responsibility for the transmission of COVID-19 to the rest of the world – a discussion that has become politicized, according to Xuan Li.

“While undergoing a pandemic, it makes perfect sense for countries to compare in order to figure out the right way to handle the crisis,” she says.

“However, you have to keep the discussion at a scientific level instead of relying on politics and feelings. Otherwise, the discussion can turn into hate, and hate transmits faster than any virus.”

Xuan Li says that, initially, she was critical towards the government herself. But that changed as time passed and the authorities got the virus under control.

“I think the Chinese government has done a remarkable job in handling the virus because of its swift actions, and I believe there’s a convergence in the way that governments have been taking rigid and strict measures in hand as COVID-19 spreads,” she says and goes on:

“I also believe the discussions on the origins of the virus quickly become a blame game where people with different cultural and geographical backgrounds have different opinions.”

Locked up with her family

Back in the apartment on the 29th floor under the lockdown in Wuhan, Xuan Li and her family managed to prevent the atmosphere from getting too oppressive.

“We were six family members living together in our apartment, covering 160 square meters: my parents, three other relatives and myself. And of course, at times the atmosphere around the apartment was pretty tense since we had to live close together for an uncertain amount of time,” she says.

“However, I focused on the positive aspects of it all. I’ve been living in Copenhagen since 2016, and I rarely get to visit my family. So finally, I could spend a lot of precious time with them.

Since we had to keep ourselves inside the gates of the apartment building, we couldn’t go to the grocery store

“And when things got a little intense, I kept myself busy by revising and publishing academic papers and writing a job application for the position of Postdoctoral Researcher at CBS,” Xuan Li says and continues:

“I wasn’t bored. Some of my family members were, though. They didn’t do much other than sleeping, eating and waiting for time to pass.”

And speaking of eating, Xuan Li and her family took turns cooking during the whole period. But shopping for groceries could, at times, be rather challenging.

“Since we had to keep ourselves inside the gates of the apartment building, we couldn’t go to the grocery store. Therefore, the local district authorities made the properties’ administrating companies provide and deliver groceries to the residents,” she says.

“We could also order the groceries online directly from the local supermarket. But you had to be very fast. Every evening at 10:00 PM they were open for shopping, and then you only had 30 seconds to find all the groceries and place the order before everything was sold out! So, if your internet connection was sloppy, it was too bad, and the goods were lost.”

“But now, luckily, Wuhan has healed, and the supermarkets have reopened,” she says from her new apartment in Copenhagen where she’s undergoing her second, but less rigid lockdown.

Trauma and hard lessons

A year has gone by since Xuan Li was trapped in the apartment in Wuhan. She returned to Copenhagen three months ago, moved into a new apartment and started her new job at CBS. And after returning, she has begun reflecting on the many cultural differences between Denmark and China when it comes to managing COVID-19.

“The regulations here in Denmark are less strict than in China. When we say ‘lockdown’ or ‘quarantine’ in China we mean it literally – that you’re are not allowed to step outside and leave your house, which completely limits your mobility in a locked area,” Xuan Li says and goes on:

“Whereas here in Denmark, you can still go to the supermarket, take the bus and go for a walk in the park. So, in terms of regulations, everything is more doable here.”

That said, Xuan Li underlines that the significant differences should also be seen in a wider context. To a large extent, they rely on demography.

People in Wuhan are still holding on to their anti-coronavirus habits

“Moreover, you also have to include geographical differences and population density. In China, even a single case of infection per day is alarming and taken extremely seriously by the government because the virus can easily transmit rapidly at an exponential rate due to the density,” she says and continues:

“In Wuhan, for instance, there are 11 million citizens living in an area of 8,494 square kilometers. This means that it’s very difficult for people to keep a distance from each other, which means that even a few cases can have major consequences. And that is also why tougher measures are needed there than in Denmark.”

“Even though all the restaurants, shopping malls, bars, museums and movie theatres have reopened in Wuhan, people are still extremely cautious. They continue to wear masks and use hand sanitizers wherever they go – even in summer when the temperature easily hits 38 degrees.

“People in Wuhan are still holding on to their anti-coronavirus habits. Like myself, they have been traumatized by witnessing how fast the virus was transmitted and caused thousands of deaths, while the hospital capacity was stretched to its absolute maximum. No one in Wuhan wants to go back to that. Therefore, people have learned their lesson the hard way and continue to take all the measures they can to prevent the outbreak from returning,” she says.

And Xuan Li does the same… Or at least, sort of!

What the ****?

Therefore, when her plane from Wuhan landed in Copenhagen, she was also wearing a mask at all times – to the great astonishment of the Danes she passed by.

“When I was wearing a mask on the street, I noticed a lot of people staring at me. And I was like ‘What the ****?’, because I don’t care what people think of me whatsoever,” she says.

However, over time Xuan Li has begun to adopt a more relaxed relationship with COVID-19.

“I guess that wherever you are, you gradually become absorbed by the environment you find yourself in. At least, that’s my experience and I’ve lowered my guard a bit,” she says.

She still wears a mask, though, but if she briefly removes it to take a picture for her WeShare profile, her parents quickly respond with a finger-wagging.

“Once I posted a picture and my parents called me and said: ‘How dare you not wear a mask on the street?!’ And even though I tried, it was difficult to explain to them that the situation in Denmark can’t be compared 1:1 with China because of the much lower population density and better possibilities of keeping your distance here,” Xuan Li says.

“And although the number of cases has now notably decreased compared to December, my parents are still not convinced that it’s OK to ease one’s own restrictions a bit. And I think that’s a pretty good indication of how big a role geographical, cultural and demographical differences actually play when it comes to our behavioral patterns during the pandemic.”

“Nevertheless, my family and I have all been lucky and we overcame the fierce outbreak in Wuhan last year, and to the extent possible, we’ve all started having more or less normal everyday lives. But we’re doing everything with greater caution than before,” she says.

(Private photo: Xuan Li)

Comments