Here’s what you need to know about the master’s reform

Illustration: Ida Eriksen

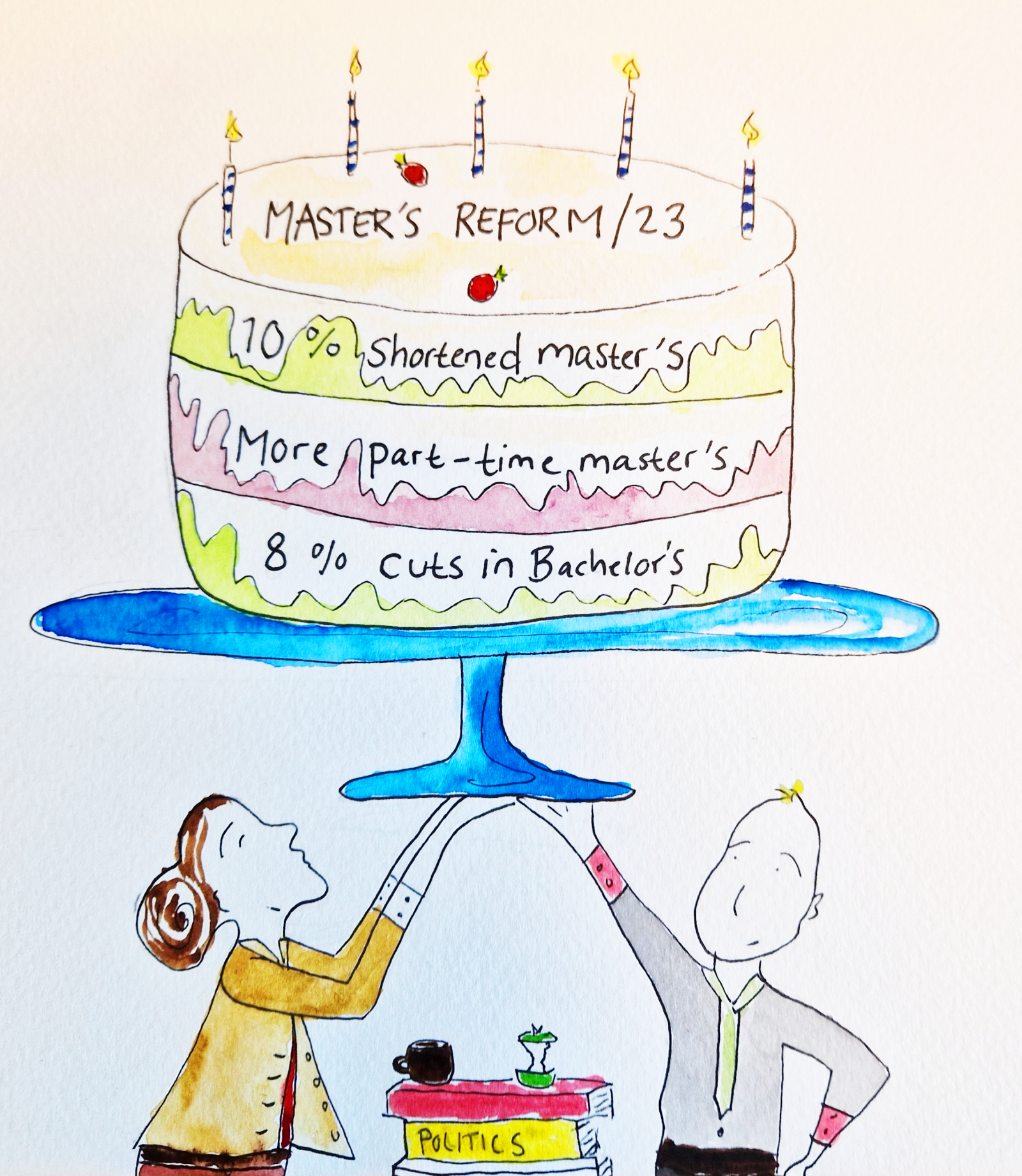

The political parties behind the master’s reform have adjusted their original proposal to shorten or reorganize up to 50 percent of master’s programmes after pressure from CBS and the other Danish universities. Fewer shortened master’s and longer to implement changes are some important revisions to the reform. CBS’ president is pleased that the government and other parties behind the reform have listened to some of the critique given by the universities but raises concern about cutting more study places in bachelor’s programmes.

How to educate new generations most efficiently and in a way that aligns with labour-market supply and demand in society is a puzzle that most governments in Denmark have tried to solve.

In March 2023, the newly elected three-party government outlined its initial proposal on how to improve options for learning throughout your life, how to attract more international students, and how to encourage students to attend more corporate part-time master’s.

Among their concrete ideas were shortening or reorganizing up to 50% of all master’s programmes at Danish universities. The new shortened masters were to be completed in one year and three months instead of two years.

In late June, the government, together with several other political parties, presented the final plan for the master’s reform. In the agreement, the parties still propose to reduce the duration of master’s programmes but they have settled on only shortening 10% of master’s programmes from two years to one year and three months (75 ECTS points).

This change pleases CBS President Nikolaj Malchow-Møller:

“CBS and the other universities have fought for a significantly smaller conversion percentage than originally proposed. We have now landed at a level which is much more realistic and responsible, and with a gradual phasing in from 2028 to 2032. I am very happy to see that our dialogue with the ministry and the parties behind the agreement has had an effect,” he says to CBS WIRE.

The newly accepted reform also promises to preserve the Rate 1 increase, which secures an additional DKK 300 million for the humanities and social sciences every year. This Rate was first effectuated in 2010 and has been prolonged every one to three years since.

“That the reform will make the Rate 1 increase permanent is indeed good news and means that CBS will not have to worry every year about whether we will or will not receive DKK 60 million in education funding,” says Nikolaj Malchow-Møller in an article on cbs.dk: Politicians agree on a framework for the master’s programme reform.

Scepticism about cutting study places

Nikolaj Malchow-Møller is happy that the political parties are considering how to make lifelong learning more accessible through the Danish educational system.

“Society is changing. We live longer. We don’t necessarily retire at the age of 67 anymore. And the technological development is accelerating. In other words, we need to learn continuously throughout our entire life. This political agreement is the first small step towards an educational system that supports lifelong learning more,” our CBS President says.

However, he is not so positive about the fact that the parties behind the reform want to cut 8% of study places in BA programmes across the universities from 2025.

“I don’t believe the demand for university graduates will be lower in the future. Unemployment rates for graduates are generally low at the moment, and the number of study places are already being reduced due to a former political agreement,” Nikolaj Malchow-Møller says.

CBS students who are already enrolled in an education programme won’t have to worry, he underlines.

“We just welcomed 3200 new BSc students at CBS and they are enrolled in the traditional bachelor programmes and will have legal claim to the current two-year master programmes. It’s the students enrolled in 2025 who will be affected when they reach the master level in 2028,” Nikolaj Malchow-Møller explains.

Director of CBS Nikolaj Malchow Møller. Photo by Anna Holte

Which master’s and bachelor’s programmes will be reduced has yet to be decided by the newly appointed Master’s Programme Committee with representatives from the universities in Denmark together with students and representatives from the Ministry of Higher Education and Science.

“We don’t know how much CBS will have to reduce yet. One of the tasks of the master programme committee will be to distribute the eight percent among the universities and the agreement states that when doing so the committee shall take unemployment rates into particular consideration,” Nikolaj Malchow-Møller says.

That could be good news for CBS, as the unemployment rates are generally low compared to other universities.

Comments