Have you seen the hidden sexism?

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

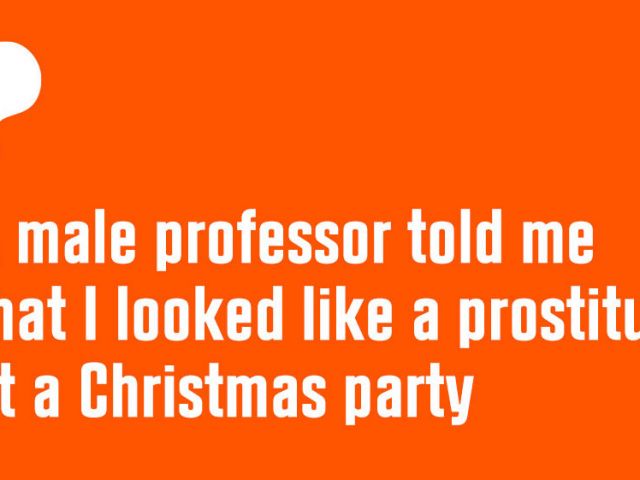

An unwanted hand on the thigh or a degrading comment about one’s gender are examples of hostile sexist behavior. However, eradicating this behavior and sexism more broadly does not necessarily start with the predators, as stereotyping by gender can lead to another, hidden kind of sexism, argues CBS researcher, Florian Kock.

Women are fragile and should be protected. Women must be presentable in public. Women should study some soft sciences.

These are examples of what Associate Professor from the Department of Marketing, Florian Kock, calls precriptive stereotypes. And if you ask him, it is the sexist stereotypes that we as a society would want to deal with and change if we wish to eliminate the hostile sexist behavior described in the Danish media lately.

“What is very important about sexism is that it often goes unnoticed. When we talk about sexism, like now, it’s the very obvious and morally disgusting cases that are reported in the media, a sexism type referred to as hostile sexism. But we also have the more hidden type – benevolent sexism,” he says.

Florian Kock is exploring the nature, causes and consequences of sexism in his research and teaching, and recently published a scientific article about sex tourism in the journal of Travel Research.

He explains that what he also refers to as ‘hidden sexism’ stems from assumptions that turn into stereotypes that – mostly subconsciously – are used to categorize one another.

“When it comes to sexism, we often talk about stereotypes. Some judge women by their looks – ‘look at her hair, she doesn’t invest in herself’. And that’s based on the assumption that women should look a specific, feminine way, which has become a stereotype,” explains Florian Kock and gives another example:

“If you are continuously told by your social environment and the media that you should rather pursue studies within “the soft science”, rather than math or tech-related subjects, because it’s nerdy and masculine, those assumptions can change your behavior and lead to self-stereotyping. ‘Because of my gender, I don’t do this or that’. And this is also sexism, but it’s harder to detect.”

“If a man in a leadership position gets angry, he often gains respect”

Florian Kock explains that we even use stereotypes to help us to navigate in the world.

For example, when we encounter a person, we subconsciously make assumptions about that person based on the gender, appearance, work title and what we know about similar people.

He has specifically been working with a stereotype content model designed by researchers from Princeton and Harvard in 2002. The model aims to understand the nature of stereotypes, and argues that for everyone we encounter, we judge how warm and friendly and how competent that person is, whether we want to or not, and thereby stereotype the person.

“Studies based on this model have shown that business women are seen as competent, but also as cold and unfriendly. The rational is that she must be very hard and tough to get into such a position, and therefore she cannot be a nice person. It can also work the other way around. Older women, like grandmothers, are perceived as warmer and more caring, but are they seen as competent? Probably not. The same goes for ethnicity, where studies have shown that Asians are stereotyped as very competent and ambitious, but are not liked,” he says and continues:

“The fact that people are stereotyping to simplify the social world cannot be used as an excuse, and we must work actively against it. And that’s an ongoing struggle and why we still have issues with sexism, because it often happens subconsciously.”

The stereotypes created stem from expectations of one another, according to Florian Kock. And some expectations have been told again and again, so that they are hard to disregard.

These pre-descriptive stereotypes are the root of the problem

Florian Kock

“If a man in a leadership position gets angry, he would often gain respect, as he knows what he wants. If a woman in the same position gets angry, some may think she’s out of control and can’t control her emotions. This is also known as the backlash effect, where women are punished for the same behavior that is appreciated in male leaders’ behavior,” he says and continues:

“People are not saying that women are bad leaders, but they subconsciously act like it, because they can have these embedded stereotypes about female leaders.”

A blank slate

On the subject of what is the most important thing to investigate from a research perspective when it comes to sexism, Florian Kock answers:

“The most important question is how do we get rid of these, often deep-rooted, stereotypes,” he says and continues:

“Sexism and other forms of derogation all boil down to three psychological parameters: Thinking, feeling and doing. So if we want to change the doing, the hostile sexist behavior, we must change the feeling and thinking as well. Because why is it that we have certain expectations of women and men? Why do I expect that I can’t cry as a man? Or why do we expect women to behave in a certain, feminine way? These prescriptive stereotypes are the root of the problem.”

Florian Kock does not have a definitive cure for this problem, but he says we must start early on pointing out the stereotypes when we see or hear them.

“It’s a long way, and the first step is to make people aware and start reflecting on our own assumptions,” he says.

But will we ever be rid of sexist behavior?

Florian Kock is thinking for a little while.

“So there are different philosophical opinions on this. First, the blank slate proposes that we aren’t born with any of these pre-wired motifs. If that’s the case, we can be optimistic, as it then depends on how we raise people,” he says.

Comments