Disaster research

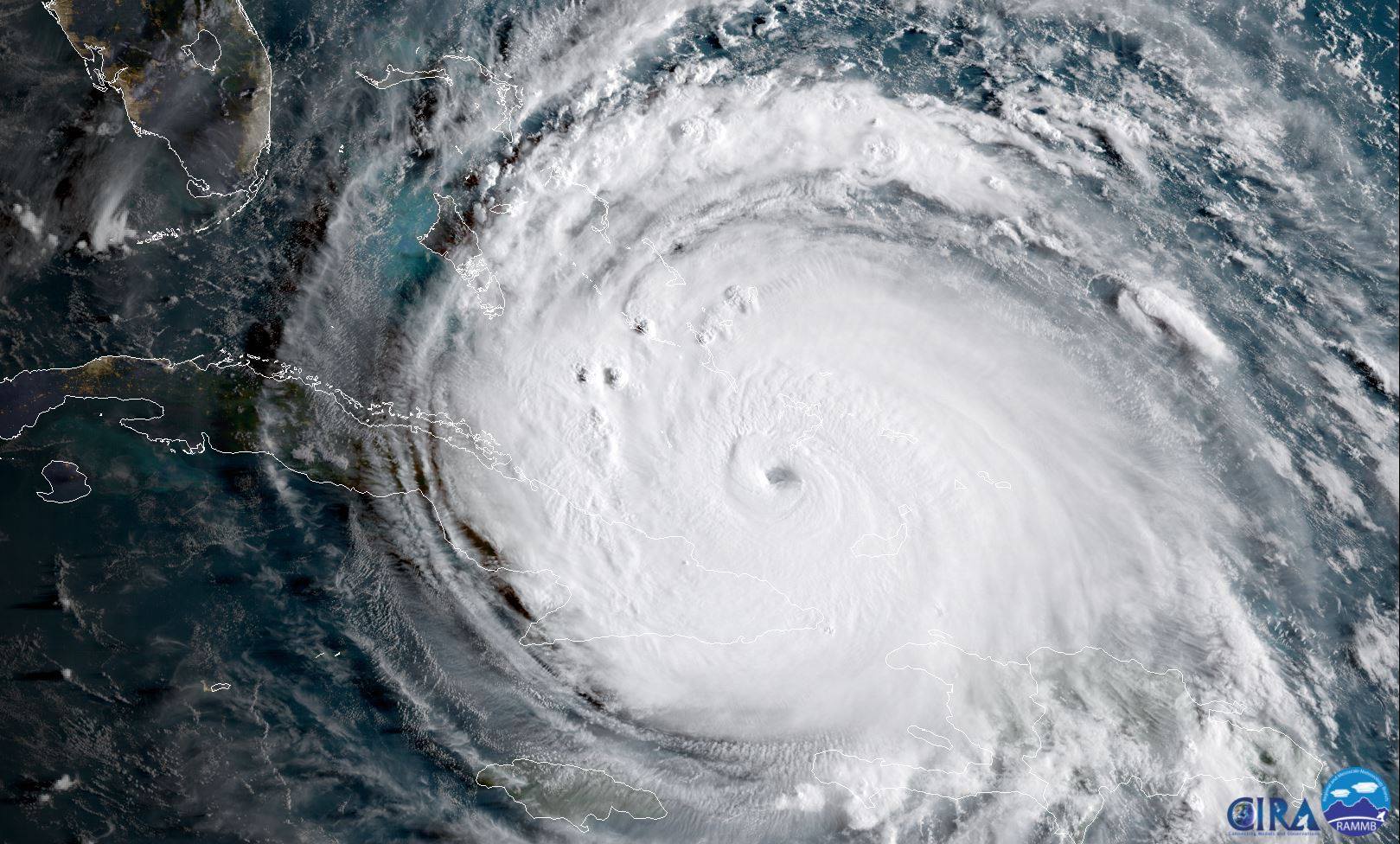

The category 5 hurricane Irma caused havoc in the Caribbean region. The aftermath is what interests disaster-researchers. (Photo: NASA - NOAA/CIRA)

Research into disasters are more evident than ever. Kristian Cedervall Lauta and Morten Thanning Vendelø, both researchers from University of Copenhagen and CBS, are part of a joint research center investigating the aftermath of devastating disasters, by trying to understand why they happen and how they affect us.

Residents from the Caribbean region have been hit by one hurricane after the other during this Autumn season, leaving entire cities under water, without electricity, and making hundreds of thousands of people homeless.

In Denmark, we haven’t had destructive hurricanes raging, instead two American students died in the harbor of Copenhagen after being hit by a jetskier.

The events have been described as disastrous and devastating – which they are – but the events are also of good use in terms of research.

In the trails of the disasters, questions are asked. Why did it happen? How did a simple act turn into an absolute disaster with a fatal outcome? Who’s responsible – if any at all? These are some of the questions researchers from CBS and the University of Copenhagen seek to answer at COPE – Copenhagen Center for Disaster Research.

“Research into catastrophes is, in many ways, quite fantastic as its relevance is self-explanatory. As more people crowd together in cities and along the coastlines, they become vulnerable to disasters. And we are seeing a quadruplication in disasters compared to just 30 years ago. So, it has a natural relevance as a field of research,” says Kristian Cedervall Lauta, Associate Professor in law at the University of Copenhagen and chair of COPE.

Emergency food

Morten Thanning Vendelø, Professor at the Department of Organization, and one of the founding fathers of COPE, has a package of compact emergency food in his office. Not in case of a national disaster though.

We need a disaster before changes are made

Kristian Cedervall Lauta, Associate Professor, University of Copenhagen

It was given to the participants of the first event held by COPE on the 21st of December in 2012.

On that date, the world was, according to the old Mayan calendar, supposed to perish. So, obviously, it made sense to gather a bunch of researchers from different fields and have an event about catastrophes.

“Catastrophes are – believe it or not – very rewarding to work with in the sense that you, as a researcher, have access to different kinds of data such as investigation reports. In this way, we can work faster because others have already gathered material. Disasters don’t stop happening, and we want to help explaining why they happen,” says Morten Thanning Vendelø, Professor in crowd safety and crisis management.

Interdisciplinarity is needed

At COPE, they have researchers within fields, such as, theology, anthropology, law, economics, and organization to combine their theories and expertise in order to give a better understanding of what follows after a catastrophe. Whether it be caused by the incontrollable forces of nature or humans. (See fact box) And this is what makes COPE so special, argues Morten Thanning Vendelø.

“There are centers like this focusing their research on catastrophes, but they tend to be dominated by sociologist. We want to practice the interdisciplinarity and bring all kinds of researchers into the work,” he says.

Kristian Cedervall Lauta, Associate Professor of law at the University of Copenhagen and part of COPE, says that disasters can’t be studied from only one perspective.

“It makes so little sense to study disasters from only one point of view, as they don’t origin within one field. Earthquakes are not only about the forces of tectonic plates: they are results of building standards, urban planning and human rights as well. If I want to dig into human rights after an earthquake, I will naturally have to know a thing or two about how earthquakes work. I have to be interdisciplinary,” he says.

Cracks in Italy

Kristian Cedervall Lauta is curious about how catastrophes affect laws and policies in terms of reducing the effects when a similar disaster should strike again. Which is why he finds earthquakes and hurricanes of great interest.

He mentions the earthquake the caused the death of 309 people in L’Aquila, Italy, back in 2009, as one of his favorites – research-wise that is.

“After the earthquake in L’Aquila, six scientists and a government officer were accused of involuntary manslaughter. This is an interesting case, as it reveals what roles knowledge and research play in society. I followed this case for three years. The scientists were found to be not guilty, but the government official was eventually sentenced,” says Kristian Cedervall Lauta.

As Kristian Cedervall Lauta focuses on the aspect of law that is in relation to natural disasters, he also found it interesting when corruption was revealed in the wake of another Italian earthquake.

“Earthquakes have revealed that the construction industry is deeply corrupted. Companies can bribe authorities to not supervise different building projects. And in that sense, avoid a strict building regulation that is designed to prevent buildings from collapsing during earthquakes. This is interesting for me because the disaster comes to reveal how we engage and act in society,” he says.

When shit hits the fan

At the moment, Kristian Cedervall Lauta and 12 of his research colleagues are finishing a research project about how catastrophes changes societies, as there is a tendency of societies acting the same way every time disaster strikes.

“Every time a disaster hits, a matching law is made to prevent or to be more prepared for a similar event. This is meaningless. Don’t just look at one specific section of traffic lights and don’t just prepare for a hurricane coming from a specific position and with a specific strength. Maybe there is a need for a general change to actually prevent these events from happening,” says Kristian Cedervall Lauta.

It was an accident

One thing is natural disasters that strike out of thin air and another is man-made accidents. These are the kind of accidents Morten Thanning Vendelø has specialized in.

He has been investigating different accidents in Denmark, including the tragedy at Roskilde Festival, which happened in the year 2000 when nine people died during the Pearl Jam concert, and the capsizing accident at Præstø Fjord in February 2011. (See fact box)

“To me, it’s not about finding the person to blame for the accidents. I’m more interested in looking at how it affects the organization, the laws, and why it happened,” he says, and explains why the capsizing event at Præstø Fjord is a good subject for research.

“There has to be an explanation as to why it happened. Why didn’t anyone protest about sailing out that winter day? Why didn’t the students dare to complain about the decision? Maybe they didn’t even think about the consequences of going out on the water? These processes are important to understand in order to explain why accidents happen,” he says.

Currently, Morten Thanning Vendelø is involved in a research project regarding safety in the Arctic, as climate change and bad GPS-signals can cause accidents with fatal results. But he is also thinking about taking up a recent accident as a research project.

“The jet ski-accident in the harbor of Copenhagen was an accident that was just waiting to happen. People have been saying it for years that one day, people will get killed. This kind of accident could be interesting to look into, as it could have been prevented. But why wasn’t it? And did the people riding the jet ski even think about their actions as being dangerous?” he asks.

A disaster is brewing

In the wake of the devastating hurricanes Irma, Harvey, and Jose, people have been asking: are they caused by rising temperatures? Are we going to see more disasters like these? Most likely yes.

“Climate change is a catastrophe that is brewing. We might not feel it yet. But it quite likely to come,” says Morten Thanning Vendelø.

Climate scientists have been warning us for years about the consequences of rising temperatures. But still, it seems that not everyone is taking their predictions seriously. Kristian Cedervall Lauta explains why.

“Science point in the direction that we have to suffer a little before we act. We need a disaster before changes are made. It’s a bit like diets. The scale often says that we are overweight before we start eating healthier,” he says.

Comments