Bursting the bubble of success: How a global phenomenon changed a district into a bio-poor zone and created inequality

When CBS professor Stefano Ponte was trapped in Covid lockdown in the spring of 2020, he decided to study the unprecedented success of Prosecco wine as well as the hidden costs. “For those living in houses next to the vineyards, property prices are declining because no one wants to live next to a place where they spray 20 times a year," he says.

Among the steep sunny slopes of the ancient green hills in Northeast Italy, grapes are gently picked by hand on family farms, processed in private cellars or cooperatives and poured into bottle after bottle. This popular sparkly white wine, Prosecco, brings wealth to an entire community. Very picturesque right?

You might even have sipped some of this fruity nectar at New Year’s, momentarily dreaming of warm summer days.

Now imagine this picture-perfect circle from grapes to wine, to happy consumers, expanding into regional and political tensions, mixed with bio-diversity wipe-out and extensive chemical use that altered the way of life for the local population. All because Prosecco became the drink of – not the gods – but the millennials. And to any hardened fellow millennials out there, don’t worry, this article will not be more millennial bashing.

Instead, this is a story about understanding the hidden costs of great success. How businesses can affect the society around them and forever change a community.

So, what exactly happed to create all this trouble? In the halls of Dalgas Have, one man knows the answers, and CBS WIRE sat down for an interview with him.

Look beyond the success

Italian-born Stefano Ponte is a professor of International Political economy at CBS and in August he published his study “Bursting the bubble? The hidden costs and visible conflicts behind the Prosecco wine ‘miracle’” in the Journal of Rural Studies.

For 20 years, he has been researching global value chains like the wine industry in South Africa, with a focus on sustainability and power relations. He has spent time getting to know wine processing procedures in order to better understand the world of wine. Having grown up close to the Prosecco area himself, he had a front row seat to see how the local sparkling white wine rose to unprecedented success, and he recognized that there might be an important lesson in looking beyond the success.

“It’s important that we at CBS look at business in society, and not just at what superficially makes something a success. We need to understand the intended and unintended consequences that may require other people to pay some price without knowing it. I think it’s also good for businesses to know these kinds of things because trying to address that, before things get out of hand, is important for retaining your reputation, managing risk, and preserving market shares,” says Stefano Ponte.

Lockdown project

Prosecco is now produced in much of the Italian region of Veneto, and especially on the Valdobbiadene hills and in the Conegliano area. Two decades ago, it was relatively unknown internationally, but in a short span of time it has become a major player in the wine market, bringing wealth and causing vast changes to an entire region. But this boom has also come with hidden costs that are not pictured in romanticized advertisements – hidden costs that spark conflict, envy and political debate according to Stefano Ponte.

Stefano Ponte’s study focuses on what the boom has meant for the local wine industry, the local population, and politics in the region. And fittingly, the study started around the same time as the rest of the world decided to drink a bit more than usual and dream of better days: During Covid lockdown.

Stefano Ponte found himself stranded in Veneto when a planned research trip to South Africa to study the wine industry there was postponed indefinitely. Not the idle type and while working as a visiting professor at his alma mater, the University of Padua, he decided to conduct a study of the local wine industry instead.

Some of these areas are very poor in terms of biodiversity and this is now a human-made environment

“I’ve long wanted to do a side project about the wine industry in Italy, essentially looking at inequality and power relations, and in particular through the lenses of sustainability, so when Covid-19 stopped my planned trip, I decided to do this smaller project. The Prosecco project is about the hidden costs of the supply chain, especially the social and environmental costs, which may not be clear to consumers or even the government, or to external observers when you consume something,” says Stefano Ponte.

Democratic luxury

Nobody expected Prosecco to become a global phenomenon but being an affordable wine and easy to produce in large quantities, it filled a gap in the market for bubbly white wines that are not as expensive as Champagne. Today, Prosecco sales account for a third of the global volume of this segment. The production is a major source of wealth and has remained locally anchored in mostly family-owned vineyards and processed through big cooperatives, with very little foreign investment so far.

“These local entrepreneurs had something in hand that then became popular. They didn’t promote it abroad themselves. They rode the wave pretty well but they didn’t start it. It was quite fortuitous that simple, clear bubbly wines became trendy. I love Prosecco. It’s a happy wine for everyday use. The funny part is that it’s like a democratic luxury because it’s a sparkling wine, but it doesn’t cost much,” says Stefano Ponte.

At the turn of the millennium, Prosecco started becoming popular outside Italy, and the growers increased their production to the max, trying to meet growing demand. But in the early 2000s, the Italian farmers came very close to losing control of the Prosecco brand. If not for some clever thinking and legal argumentation, Prosecco would not be what it is today.

At this point we need to dive into some very titillating EU legislation and a little background on rights for the necessary input for understanding how the success of Prosecco ended up with hidden costs. Oh… and then there is Paris Hilton.

It girl ad kicked off creative expansion and political fight

Few altercations about the EU’s “Protected Designation of Origin (PDO)” have been kicked off with a celebrity cameo like Paris Hilton. But in 2006, the number one ‘it girl’ of the 2000s was hired by a British drinks company to promote a canned drink, “Rich – Prosecco” to mainly British consumers.

The ad campaign which might be the noughtiest thing you’d ever see – challenged the Italian farmers’ sole rights to use the name Prosecco. They realized that in order to retain control of the Prosecco brand and stop others from using it, they had to present a stronger regional claim. Especially since an EU wine reform in 2008 made it more difficult to get a “Protected Designation of Origin”.

“That’s really what got their act together because they thought they were losing control of how the product was being offered to consumers. They wanted to control the market and the value that they had created by selling Prosecco only in bottles. Having it sold in cans by a foreign company was not something that the growers wanted,” says Stefano Ponte.

So, to keep the brand-name protection, the growers had to prove that Prosecco wine was more than just the product from the grape called Glera but had a historical foundation and a physical origin. And as luck would have it, they found a small village called Prosecco, and evidence that a wine called Prosek had been grown in the area for hundreds of years.

Another stroke of luck for the Prosecco success story resulted from this discovery. Because the village wasn’t near the original Prosecco wine district, the decision was made to expand the Prosecco wine district to include the area of Prosecco village. This led not only to gaining brand-name protection in the EU, but also tripling the area for growing the Prosecco wine.

“They were very smart, but they were also very cheeky. The expansion was dramatic, but vital because there was huge demand, so it paved the way for incredible growth and created a huge boom in production over the past 10 to 15 years. The funny part is that the Prosek wine that they used to produce centuries ago in the Prosecco village is not bubbly. It’s a flat white wine and didn’t use the same grape variety as Prosecco,” says Stefano Ponte.

But this expansion also set in motion many of the negative effects that accompanied success in the Prosecco region, as production has now become massive.

The Prosecco invasion

The explosion in demand for Prosecco has drastically changed the landscape. Areas that previously had much less viticulture are now dominated by it, and as every available spot is being used for planting grapes, the price of land has risen. Forests have been cut down in some areas.

“If you go to the original Prosecco wine district, you will see that vineyards are taking over wherever there’s space. Vineyards are planted along the streets and walls because it is profitable. In the expanded areas, they used to have many other kinds of wine, but Prosecco is now so much more profitable that these other wines are disappearing. They actually pulled out these other grapes, so there was a big drop in diversity within what was already a monoculture. Some of these areas are very poor in terms of biodiversity and this is now a human-made environment where only one plant species is allowed to grow,” says Stefano Ponte.

Chemicals were also drifting into schools and people’s houses

According to Stefano Ponte, the Prosecco farmers did what they could to meet demand, the local population, not directly involved in winemaking, started to suffer the consequences of large-scale production. The Glera grape used for Prosecco is vulnerable to fungi because of the wet climate and needs to be sprayed with fungicides up to 20 times a year, and the farmers were not always very considerate of their neighbors.

“For those living in houses next to the vineyards, property prices are declining because no one wants to live next to a place where they spray 20 times a year. Chemicals were also drifting into schools and people’s houses. And residents started protest committees to complain to local politicians about not being able to go into playgrounds for two to three days after the spraying,” says Stefano Ponte.

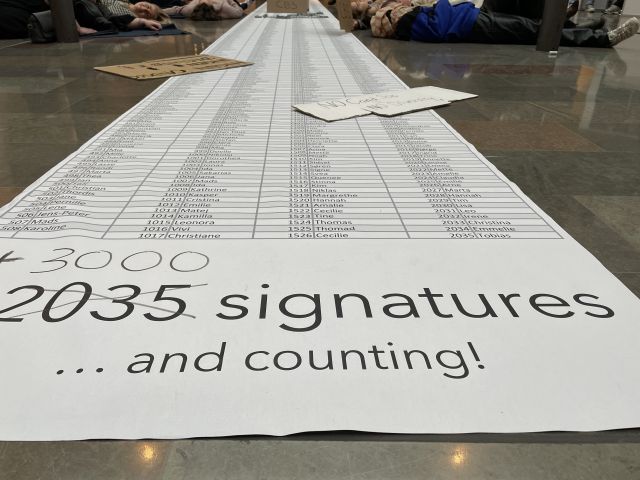

Luckily, according to Stefano Ponte, there seems to be no scientific evidence that the spraying endangered people’s health in the area, but a crack had appeared between those benefiting and those affected by the rise in production. Locals started protesting about the negative effects of a flourishing wine industry that didn’t share its wealth around.

“There was this realization that a lot of people in the Prosecco area who weren’t involved in the production thought: “We’re getting screwed here”; so it became clear that something needed to be done so that they could also benefit. In the political realm, there was a sense of injustice and inequality because the grape growers and winemakers were raking in money, and of course they were also employing people, which was good. But anyone not involved was only getting the externality effect, in other words, the short end of the deal,” says Stefano Ponte.

Going green in a dead zone

The study shows that things have slowly started moving in the right direction because of these protests. Local committees pushed politicians to introduce legislation calling for precision spraying in residential areas and for farmers to alert residents before spraying.

“Normally, when the demand for change is implemented in the global value chain, it comes from consumers, so it’s interesting to see these changes happening because of local protests,” says Stefano Ponte.

Some Prosecco growers are also trying to be more sustainable, and many farms take pride in having solar panels and electric vehicles as a part of their production systems.

“From an energy perspective, they are achieving a lot, and that’s great. Some of these winemaking operations are incredible because they have the resources to invest. They are green in that perspective, but if you go into the field, a lot can still be done to be more sustainable and biodiverse,” says Stefano Ponte.

There was this realization that a lot of people in the Prosecco area who weren’t involved in the production thought: “We’re getting screwed here”

Prosecco’s massive success has also increased tourism in the wine district. Politicians and wine growers in the Valdobbiadene and Conegliano areas successfully applied for the hilly area to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019. But according to Stefano Ponte, this is a somewhat hollow distinction.

“The idea was to do something for diversity and preserve these very picturesque hills and create value out of the romanticization of what they call ‘heroic agriculture’ – cultivating by hand on very steep hills. But the expansion of production has also changed the area. In some areas, forest cover has been lost and some of the expansions have caused soil erosion. In a way, with the UNESCO site, they are trying to preserve a landscape that has already been transformed,” says Stefano Ponte.

A long way to go

Even though a lot of tension persists, Stefano Ponte believes it would be wrong to think of the Prosecco story as a purely negative tale. He did not set out to look for a scandal in Prosecco. Yet, as he says: “My work is about trying to peel off layers of complexity, because sometimes at business schools, we tend to look at these great success stories uncritically. If we stay too much on the surface, we don’t really understand the deep socioeconomic and environmental dynamics taking place. We need to know the true impact so that consumers, governments, civil society, and businesses really know what is going on,” says Stefano Ponte.

Comments