Applying for research grants is a losing game researchers must play: “It’s a lottery”

“The funding landscape in Denmark is peculiar in one sense because of the big role of private foundations in funding research. And at the same time, it’s also something that many other countries are moving towards. Private foundations are becoming increasingly important in many other countries. If we understand what’s going on in Denmark, we may also make some predictions about what’s going to happen in other, bigger countries.” Photo: Shutterstock

2022 was a record year for external research funding at CBS. But behind every grant lie many more rejections – and hours of work – which you rarely hear about.

While doing her PhD at Imperial College in London, Valentina Tartari, now Associate Professor at the Department of Strategy and Innovation, had a supervisor who was very active in fundraising.

“That was my academic imprinting and what I’ve tried to implement during my career. I’ve always seen people writing proposals and building research groups thanks to [grants from] those.”

Valentina Tartari has been at CBS since 2012 and received her first grant, the Sapere Aude, in 2014. The grant allowed her to do a project with a research assistant and spend a semester at MIT, while she was an assistant professor.

Since, she has continued applying for grants to support her preferred research method – working in a team. With another professor, she now leads a research group consisting of a postdoc, a PhD student and a database manager. Next year, they will be joined by two more colleagues.

“I want to work with PhD students and postdocs, and in order to get them, I need to pay them. And the only way to pay them is for me to find money somewhere. I like to have a lab and work with people, not just on my own, which means you need to spend quite a bit of time on fundraising.

“That’s not the only way of doing research in the social sciences, actually, it’s probably a bit of a minority way. But this is what a lot of people are moving towards, because we need bigger investments in infrastructure, in data. And all these things cost a lot of money that the university doesn’t provide.”

Valentina Tartari’s experience of research funding comes not only from applying for it – she also studies it.

Valentina Tartari prefers doing research in a group, for which she needs external funding: “It’s a lot of work to have postdocs and PhDs. You have to follow them and be mindful of their career. And you end up helping them. If they stay in academia, it’s a kind of a bond that goes on forever. So, it’s a big investment as well.” Photo: Caroline Hammargren

As an economist in the field of science, she looks at how knowledge is produced in universities and then commercialised to become technology.

“I study scientists and how they produce knowledge, so the funding system is part of that. My interest is in how different institutions affect the kind of science and knowledge we produce, and how that knowledge is disseminated to society, to industry. So, for me it’s interesting to understand how different configurations of the funding system may give different outcomes in terms of what we produce, but also different outcomes in terms of who participates in science.”

One of her current projects is called The Effects of Research Funding on the Rate and Direction of Science. The natural sciences depend much more on external funds. Research is conducted in groups of researchers and requires equipment, materials and laboratories.

“Natural science research is very, very expensive. Conducting social science research has not been as expensive – we don’t need laboratories.”

But, she says, there is a shift where expensive data, servers and external funding are becoming more important. It may be harder for social science researchers to do research without funding in the future.

The journey also matters

Indeed, external funding is on the rise. 2022 was a record year for external research funding at CBS with grants totalling DKK 211 million, compared to DKK 150 million in 2021.

The increase is due especially to a few large grants, including DKK 59.4 million for The Center for Big Data in Finance (BIGFI) funded by the Danish National Research Foundation. CBS also received a record amount of funding from the EU.

CBS’ strategy is to increase its external funding. The goal is to obtain grants worth DKK 162 million per year.

In that, the Research Support Office (RSO), a fourteen-person office located on a quiet floor of Porcelænshaven, is instrumental.

Their main task is to assist CBS researchers with funding applications. The office is divided into teams covering national funds, private funds and European funds – the main funding streams from which CBS gets its external funding. They screen for appropriate funding calls, help match up researchers with opportunities, and then support them in putting together applications for submission. If funds are awarded, they also help with contract agreements.

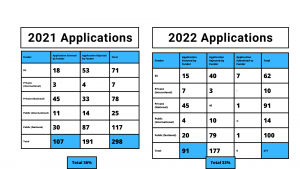

Development in approval rates 2021 – 2022. Source: Research Support Office

Applying for research grants can take up a large share of academics’ time. Researchers at Danish universities spend on average 9% of their work time applying for external funding.

Valentina Tartari has found the Research Support Office useful – especially for drafting the budgets.

“It’s not the same as writing a paper, so it requires a bit of experience. It needs to be tailored to the funder that you’re submitting your proposal to. You need to understand what they want, what’s going to work with them, what’s going to interest them. It takes a lot of time.”

On top of that, the likelihood of getting the money is small.

“Sometimes it’s very close to a lottery, especially for the most elite funding. So, you need to decide if you want to allocate your time to something that has a very small chance of success. And that is time you have to find yourself.”

Photo: Shutterstock

While more funding sounds positive, it is not without its challenges. A new report from DEA, a think tank established by the Danish Society for Education and Business (DSEB) highlights some of the side-effects of external funding – for researchers and research.

Too much competition for external funding could mean universities lose promising young researchers. Less risk appetite among funders may lead to missing out on potentially valuable but high-risk research. And the more universities depend on external financing, the less they are able to independently prioritise and steer their research.

In addition, bringing in external funding has a financial cost. The University of Copenhagen estimates that for every DKK 100 of external grants brought in, the university has to spend DKK 70.

A life of disappointment

While the CBS homepage often features stories about new research grants, a more common story, which rarely makes the headlines, is that of rejections.

Secrecy around applications is not uncommon.

“I don’t like to give away my ideas either, but I don’t mind people knowing that I apply. Even if I don’t get it right, I don’t feel ashamed.”

Perhaps it helps that she studies the subject, and has been successful, though she has also been rejected.

“It’s always a disappointment. Academic life is full of disappointments. We send papers that are rejected most of the time. We send applications that are rejected most of the time. It doesn’t matter how many times you experience it, but that’s the way it is in a sense.

“They are your ideas, right? It’s not nice when people tell you that your ideas are not good enough.”

While academics may have to live with rejections, she believes universities could help ease the blow.

“There needs to be some incentive and reward built in, even for the people who are not successful. Otherwise, you’re rewarding people based on a lottery.

Do you think CBS could do more to value the failed applications?

“They should put more value on the act of applying for funding, because that’s the one that requires effort.”

Specifically, she thinks, giving researchers more time to spend on applications.

If at first you don’t succeed…

Rejections are also something Valentina Tartari studies in one of her research projects.

“One thing about funding is that most of the time you don’t get it. And because we’re human beings, we don’t like rejections. So, who persists? Who keeps asking for money, especially if you’re in fields where you can’t do research without external funding, like the natural sciences? If certain groups are disproportionately likely to leave the race, then by giving all those rejections, we’re actually discouraging them very early on from pursuing a scientific career. We may end up with some imbalance in the system. I think this is something that is interesting to understand.”

Her project has just started, so she has no findings to share. But one question she is exploring is how much the funding system is responsible for the gender gap in science.

On the table in her office, a blue and red portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsberg in fuse beads leans against the wall. By her picture, the quote: “Women belong in all places where decisions are being made” is written. She says she likes to have it there for her female students to see.

For once in her career, Valentina Tartari is not spending late hours on funding applications. Only when asked to support or peer review for colleagues – also a part of the application process.

But external funding will most likely be part of the game for the foreseeable future – perhaps to some an unfair lottery, but one that values grit.

Or as Valentina Tartari puts it:

“What they tell my younger colleagues when they apply for funding is that you just don’t take no for an answer, you try again. That’s the only way. Persistence is the key.”

Comments